Lt Col Simon R Sinnreich, America’s highest ranking Jewish officer during World War II, had a similar take.

Our family didn’t know him during that era, but Si and his wife Emilie became close friends of my parents soon after we moved to Long Island in 1956 - a friendship that lasted to the end of their lives and has continued into the next generation of Sinnreichs and Stodolas. Although it wasn’t easy to get Si to talk about the War or his service in Europe, my husband, who has a gift for drawing people out, once asked him how many troops the generals were prepared to lose in the Battle of Normandy. Si’s answer was stark and simple: “As many as it took.”

For most of us, the term "D-Day" evokes haunting images of wave after wave of landing craft approaching the Normandy beaches, of the hapless paratrooper left hanging for hours after his chute became entangled on a church steeple in the nearby village of Sainte-Mère-Église, and of course of the Normandy American Cemetery with its seemingly endless expanse of crosses. On this 75th anniversary of D-Day, when solemn military ceremonies and moving first-person accounts by the few remaining veterans, now in their nineties, flood the media, these heroic exploits and appalling sacrifices claim most of our attention.

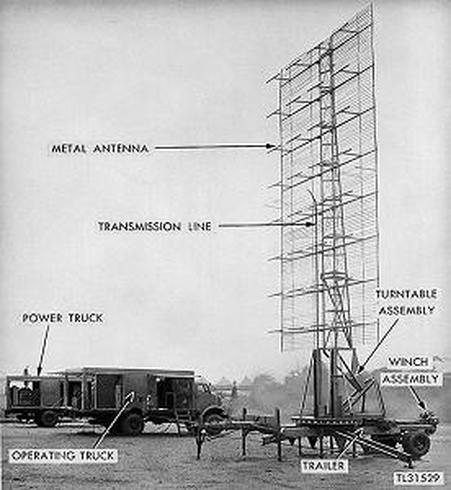

To induce Field Marshal Rommel to hesitate or possibly even to deflect the German Panzer Divisions to the wrong place, Eisenhower stationed a shadow invasion fleet in Northern England, complete with dummy inflatable tanks, and leaked misleading information through his network of spies to suggest the invasion would take place at Calais, not Normandy. He knew, however, that this ruse would not be enough to deceive Rommel, because the Nazis had radar units all along the French coast searching for signs of an invading fleet. The Allies' only hope of evading these tireless sentries was to destroy as many of them as possible and then to use the same strategy of adding competing information to the mix.

The radar scientists at Camp Evans, along with their counterparts in Great Britain, the US Navy, Harvard, and MIT, were tasked with developing the equipment needed to carry out these plans. Their efforts enabled bombers to zero in on German radar sites, to interfere with (jam) their communications, and to introduce confusion by dropping “chaff” - mostly strips of aluminum - to create a cloud of indecipherable images on Nazi radar screens, ploys that caused Rommel to delay sending Panzer Divisions to Normandy long enough for the Allies to establish a beachhead. As a result, the German air response was next to non-existent. In addition, radar sets designed at Camp Evans landed on the beaches to protect the troops as they fought to fend off Panzer attacks.

By D-Day, radar and its military uses had clearly come a long way in both sophistication and precision since the Chain Home network described in my most recent post. Using radar not only to obtain information but to spread disinformation, then called radar countermeasures, is now known as Electronic Warfare or EW, the field in which my father continued for the remainder of his career.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed