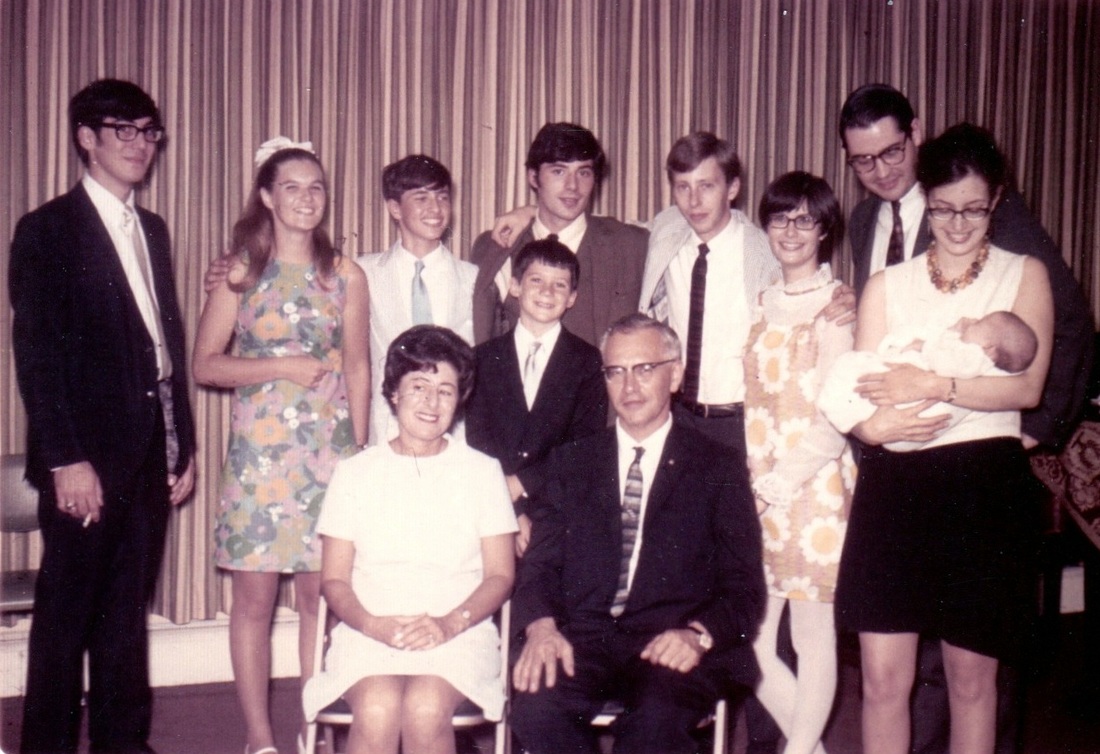

The following entry is adapted from a piece I wrote two years ago to commemorate the 100th anniversary of his birth, October 31, 1914. The original article appears elsewhere on this website but I am reposting it here on his birthday for those readers who are only here for the blog, and because some things bear repeating. For my fellow lovers of vintage photos, I have added several of my dad and his family.

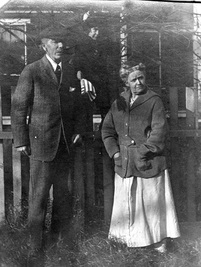

My dad with his maternal grandparents. Chasing butterflies with his granddad was one of his few childhood memories.

My dad with his maternal grandparents. Chasing butterflies with his granddad was one of his few childhood memories.  Photo of Beatrice King and Edwin Stodola, from a brochure showing them in performance.

Photo of Beatrice King and Edwin Stodola, from a brochure showing them in performance.

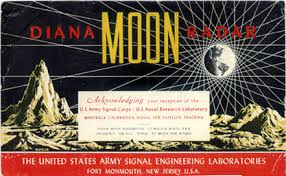

On July 22, 1939, he and my mother, Elsa Dahart, were married by Dr. A. Powell Davies, a distinguished member of the Unitarian pantheon, at the All Souls Unitarian Church in Washington, DC. At the time he was working for the War Department assigning radio frequencies for Army facilities ("boring!"). Later, seeking a more research-oriented job, he accepted a position in signal detection and the development of radar at Fort Hancock in Sandy Hook, New Jersey, and my parents relocated to the Jersey Shore town of Long Branch. After Pearl Harbor, when the country moved to a wartime footing, his work was transferred to the Evans Laboratory in Belmar and my parents moved to nearby Neptune.

In Neptune, we were part of the small year-round population of a summer beach resort community where a lot of homes stood empty all winter. Today it is all paved roads and marinas and lawns, but when I was little it was very rural - not agricultural, but mostly gravel roads where you could ride your bike and not pass any houses or see any people for long stretches. (I doubt a small child would be permitted to do that today, but - times have changed.) Yards were mostly sand and rock gardens; you couldn’t have a lawn unless you brought in loads of topsoil, which my parents and most of our neighbors never did.

Our bungalow on Pinewood Drive in Shark River Hills

Our bungalow on Pinewood Drive in Shark River Hills In 1948, my father took a job with Reeves Instrument Corporation in New York City and began several years of commuting by rail (including a running bridge game on the way in and reading murder mysteries on the way home), punctuated by frequent business trips around the country. At that point he became a weekend father, leaving my mother to shoulder most of the burdens and pleasures of child-rearing. Still, he was very much present most weekends, and my Saturday morning memories of my dad are of the lower half of his body jutting out from under his car. (Brat that I was, I used to tell him if you looked long enough and hard enough, you could probably find something wrong with almost anything.) We never needed a plumber or electrician because he was an amazing Mr. Fixit who could take on just about any washing machine or toaster that dared to break. He also became an avid outboard motorboater during these years, an interest that persisted even after we left Neptune. We had a series of vessels with names consisting of the first two letters of each of his children's names - first CYLESH and later CYLESHRO.

In 1956, Reeves moved to Garden City, Long Island, and the commute from Neptune was no longer feasible. My dad considered changing jobs at that time, which also would have involved moves (to either California or Michigan), but in the end Reeves made the best offer. And so our Jersey Shore days drew to a close.

After a little house-hunting, my parents realized they could get a better house by living further out on the island - meaning my father would once again be relegated to a 45-minute commute, this time by car. My mother thought most of Long Island was too flat and zeroed in on the town of Northport because it had hills. Our real estate agent spent a whole day ferrying us around and scoping us out before revealing that there was a house for sale at 118 Stanton Street, right next door to her own home. It was truly a wonderful house, with a bay window, a Dutch front door, knotty pine paneling, a beautiful tilework fireplace, bedrooms with special features (mine had an outdoor balcony and Leslie’s had a loft), and a huge green yard, a novelty for us. We all fell in love with it immediately. A bonus, especially for my dad, was an active Unitarian fellowship located just a few miles away in Huntington; it was the first time we'd ever lived closer than an hour's drive to the nearest Unitarian church. Another bonus was the opportunity to pilot the latest CYLESHRO across the 8-mile expanse of the Long Island Sound (usually including one of his typical drive-in, drive-out visits to friends in Connecticut - which turned into fly-in, fly-out visits after my mother died and he took up flying).

My parents’ relationship was amazingly harmonious, something enough others have commented on to convince me I’m not selectively forgetting unpleasant moments. I never remember hearing them argue, let alone raise their voices to one another. I tended to attribute this to submissiveness on my mother’s part, but having watched my father’s equally courteous behavior towards his second wife, Rose, whom he married three years after my mother’s death in 1965, I think it also speaks to his fundamentally gentlemanly nature, as well as to his proclivity for choosing gentle and forbearing women as his life partners.

A running joke between my parents was my father’s nickname for my mother, Blondie—not because she was blonde (she wasn’t), but because they in some way identified with the comic strip characters Dagwood and Blondie Bumstead - Blondie handing Dagwood his briefcase and hurrying him into a catapult positioned to propel him out the front door in time to catch his bus; Dagwood constructing and wolfing down monster three-layered sandwiches with revolting combinations of ingredients; Dagwood providing endless exasperation-cum-amusement for the long-suffering ditzy-but-wise Blondie. (As I sit here remembering things like my father’s collection of dog ticks in a jar of kerosene, which he showed off like a trophy as it grew bigger over the course of the summer, I think maybe this metaphor wasn’t so far-fetched! Dagwood could surely relate to that. But my mother, though long-suffering and wise, was never ditzy. Still, that was part of the joke.)

Although both his wives were mild mannered and softspoken, my father always admired high-powered professional women immensely and counted many among his wide circle of friends. It was from him, much more than from my mother, that I received the message that women could do anything and be anything they chose. (My mom used to joke that it’s just as easy to love a rich man as a poor man – at least, I think she was joking!) He strongly urged me to take all the math and science I could cram into my schedule and made sure I enrolled in AP physics and AP calculus, something I’ve never regretted as it has opened doors that would otherwise have been closed to me.

My father's gadgeteering proclivities led to numerous patents - the most lucrative being an electronic thermostat, an updated version of which can still be found in most houses. The patent was infringed on by Honeywell, which reverse-engineered the product and marketed it on a scale beyond anything Reeves Instrument could have dreamed of. My father won a court case against Honeywell, resulting in a royalty stream that lasted for many years. He always said he had the best of both worlds with this arrangement and claimed it put me through college.

Sometime during the 1970s, my father’s career took a disastrous turn. Back in 1955, Reeves had merged with Dynamics Corporation of America. When the electronics industry fell into a deep slump, the merged operation pulled up stakes and moved to Florida in hopes of riding out the downturn by lowering expenses. It seemed to work, but not for long, and when DCA went bankrupt, it took Reeves down with it. First to be paid off were the stockholders and creditors, leaving precious little for the senior executives at Reeves, including my father, who lost their pensions. To eke out a living, he took a series of consulting jobs requiring him to live in seedy motels and tiny furnished flats all over the country, plus a more extended stint near Syracuse, New York - until he finally secured a job in Electronic Warfare at the Pentagon. All his years at Evans Lab had qualified him for a government pension, but the amount was based on his highest three years of salary, the famous federal high-3, and for him those years were 1946, 1947, and 1948. The Pentagon job enabled him to accumulate three more years, enough to provide an adequate retirement income. So his heroic efforts paid off, and in the end he landed on his feet. It wasn’t until I myself reached retirement age that I fully understood the gravity of his plight. But although he was perfectly capable of a good rant, I never heard him complain about the injustice of his situation at a time of life when he should be winding down rather than revving up.

I could say so much more about my father – his love of language and his gregarious nature, both, I think, unusual in an engineer, especially in one who was in most respects the quintessential engineer. I could talk about his encouragement of dinnertime debates and his favorite saying, “It ain’t necessarily so.” I could carry on about his love of gadgets (passed on to at least two of his four children, my brother and me) and his famous misshapen suits, weighed down by the gadgets and papers and books he stuffed in his pockets. But I will leave those threads for others to pick up and just state for the record how lucky I feel to have had him for a father.

Happy birthday, Daddy, love you to the moon and back!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed