For both full-timers like us and part-timers like the Wardells, the Shark River provided the focus of community activity in the 1940's. I practiced riding my bike no-handed down the impossibly steep (or so it then seemed) Riverside Drive hill; then, if I had a few pennies in my pocket and didn't want to ride all the way to the Cracker Barrel for a larger selection, I stopped at a little ice cream stand on the beach, now the site of a large marina. I didn't really want to swim in the river itself (because of the fierce-looking but harmless horseshoe crabs and the smaller but more aggressive crabs that given half a chance would chomp your toes), though many did; I much preferred the ocean beaches at Avon, Belmar, and Ocean Grove, with their roaring surf and vast expanses of white sand. But I loved beachcombing along the river's edge for shells and starfish and whatever other flotsam and jetsam the tides washed up. I loved building riverside sand castles and once in a while - though I rarely stopped my restless gamboling and cartwheeling for long enough to do it - basking in the warmth of the summer sun.

How the Shark River got its name is lost in the mists of time, though fanciful explanations abound. Known to the Lenape Lenni tribe of Algonquins as the Nolletquesset, it is listed on 18th century maps of the White settlers as either the Shirk River or the Shack River. Possibly its various similar names were somehow conflated, or possibly its crescent shape reminded someone of a shark. One legend had it that a large shark was swept up the river to its death in the mid 1800's. At any rate, with the dubious exception of that lone unfortunate, sharks haven't lived there at least since the Middle Miocene period, though fossil shark teeth can still be found along its banks. Certainly the possibility of a shark attack wasn't high on anyone's worry list.

Because the Shark River was the only river I knew, and because I knew it so well, it formed my entire concept of what a river is. It wasn't till I reached adulthood that I learned that the Nile, the Amazon, and in fact all the other rivers of the world were not salty like the Shark River - leading me to infer that the lowly little Shark, less than 12 miles long, was salty because of ocean backwash. Much later still, just a few years ago in fact, I learned that the Shark River is not technically a river at all but rather a tidal basin or small bay of approximately 800 acres, which accounts for its saltiness without need of my "ocean backwash" theory.

So: No sharks and not a river. Who knew?

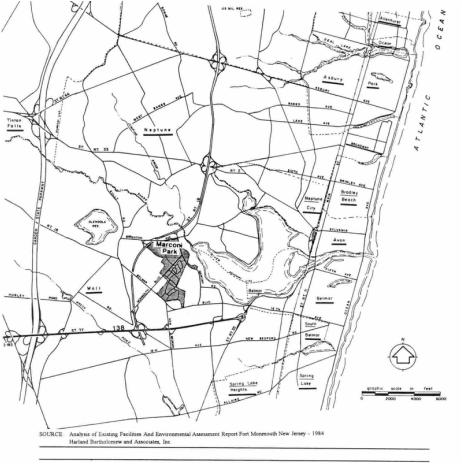

Fortunately for the future of communications, Guglielmo Marconi made it his business to know. After several months of surveying the entire eastern seaboard in 1913, he selected a hilltop on the south bank of the Shark River basin as the perfect spot for the Belmar Receiving Station, operated by the newly-formed Marconi Wireless Telegraph Company as the world's first permanent transoceanic communications center. It was located far enough from the shore and high enough to be protected from Atlantic storms. In addition, the elevation provided a low take-off angle for radio emissions, and the long-wave frequencies used at the time benefited from salt water reflection (i.e., the ocean as a "virtual antenna") for beaming signals to Europe.

The original buildings (starting with a hotel to house the workers) were completed in 1914, serving as a relay station for the transatlantic transmitting facility at New Brunswick, NJ, part of the New York-to-London link of the "World Encircling Wireless Girdle." According to a contemporary report, the station included "a mile-long bronze-wire receiving antenna strung on six 400 foot tall masts with three 150 foot balancing towers along the Shark River." Morse code messages traveled via telegraph landlines to and from the Belmar Station, the New Brunswick transmitter, and an office in New York City.

When the US entered World War I, the station was commandeered by the Navy to handle transatlantic radio traffic, a task in which it admirably acquitted itself. Following the armistice, the station was returned to Marconi's company, by then known as the Radio Corporation of America. Unfortunately, RCA abandoned the station in 1924, and the site, now fallen on hard times, was used as a meeting place for organizations as disparate as the Ku Klux Klan and the King's College, a theological school.

Then, even before Pearl Harbor, the US Army Signal Corps began a search for a new research facility. Like Marconi, the Army's communications experts scoured the eastern coastline for an ideal site. The same features that made the Shark River basin favorable for radio propagation also lent themselves to the study and testing of radar, allowing ships and decoys at sea to be used to determine accuracy and range. And although much of the original Marconi equipment had disintegrated or been removed by the time the Army's advance scouts arrived on the scene, its history as a locus of communications know-how and research must have favorably disposed them to the site.

In 1941 the property was purchased by Wall Township for the Army's use as the Signal Corps Radar Laboratory - renamed the Evans Signal Laboratory and subsequently, at its official dedication in 1942, the Camp Evans Signal Laboratory. Dozens of additional buildings were quickly built (for a total of around 134 by the end of the War). Top secret research carried out throughout World War II played a central role in the development of radar as an effective weapon for detecting kamikazes, analysis of captured German and Japanese radar, friend-or-foe identification, and other vital wartime applications. We may never know the full story of the research carried out at this facility, but it has been said that had the Axis powers known, Camp Evans would have been one of their prime targets.

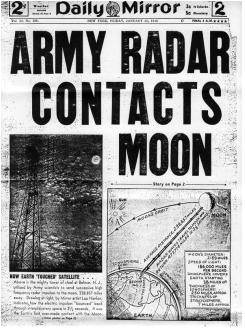

By the end of the War, the site was perfectly poised to make the leap to space communications. The world was ready for Project Diana, and Project Diana was ready for the world.

-------------

PS Happy birthday to my sister Leslie, another Project Diana legacy, who turned one year old two weeks after first successful moon bounce, and who celebrates her special day this year under the Wolf Moon.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed