Case in point: Project Diana.

Stage 1: It can’t be true.

The successful moon shot was made on January 10, 1946 but wasn’t announced to the world until January 25. Of course in those days events weren’t tweeted and retweeted at warp speed almost before they are finished happening, but still, why the 15-day delay? At least part of the explanation was offered by my father when I interviewed him in 1979, describing the immediate aftermath of the event:

“And to make a long story short, the thing came off successfully. Then we let our bosses know what was going on - and they didn't believe it! They didn't believe we'd really done it. So they called in a number of outside experts…. One of them was a fellow named Waldemar Kaempffert, who was then Science Editor of the New York Times. He was a pompous fellow. He came down and we talked with him and very quickly convinced him that we were really getting echoes from the moon. And then another man that I also kept quite friendly with, Donald Fink - he was then Editor of Electronics…. - [he] came down, and he was smart, he knew right away that there was no question about what we were doing.”

After the news was announced, Dr. Harlow Shapley, Director of the Harvard College Observatory, was asked by a reporter to provide expert commentary. Dr. Shapley termed the feat "an interesting tool in exploring the solar system" but added that astronomers were working on other wartime discoveries that he predicted would be "far more startling than the radar contact when they were announced.”

Unsubstantiated intimations of unspecified breakthroughs as yet unrevealed - thank you for that, Dr. Shapley.

Stage 3: We knew it all along.

Of course, no feat like Project Diana ever occurs in a vacuum. The War had spurred radar research in labs all over the world, on both sides of the conflict, and several other teams were poised to carry out a similar demonstration. Indeed, the great Hungarian scientist Zoltan Bay succeeded in his own attempt to bounce radar waves off the moon less than a month after Project Diana using quite a different approach, an accomplishment for which he richly deserves recognition and respect. It is an injustice to imply, however, as do some historians, that it was a colossal stroke of bad luck that Bay didn’t get there first, completely discounting the thousands of hours of work that went into making Project Diana a success - not to mention the fact that the driving force of this effort was Jack Dewitt’s “lunar love affair,” as someone put it, dating back to the 1930s. Project Diana was hardly a fluke!

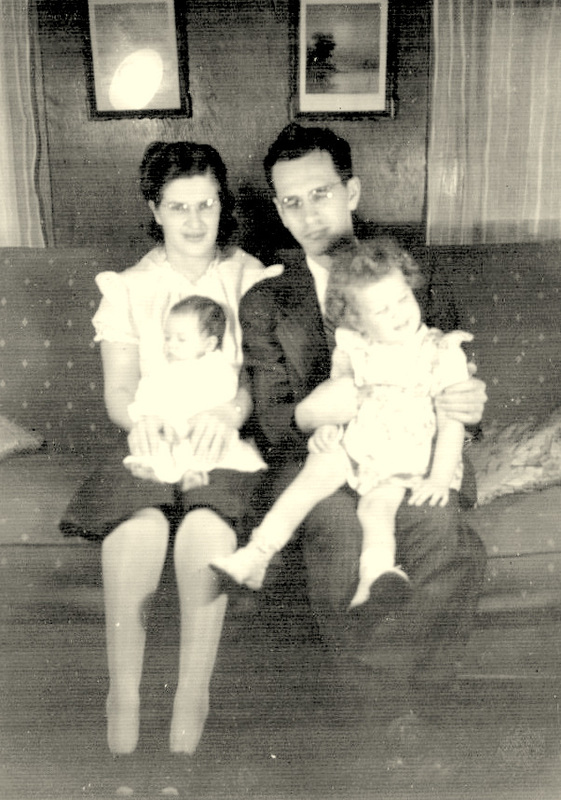

Another team that “should” have gotten there first (but didn’t) was the MIT Rad Lab - forcing Robert Buderi in his book The Invention that Changed the World, about radar but mostly about the Rad Lab, to make a 3-page detour on what he called this “Army coup” - because clearly no history of radar would be complete without Project Diana. (Buderi - who I hasten to add has been very generous in directing me to information and allowing me to quote from his book - has provided my family with an endless source of amusement by referring to my father in his account as “the diminutive, bespectacled E. King Stodola.”)

In the snarkiest twist of all, a comment was posted on the InfoAge Camp Evans website stating, “In fact, the Diana project was not first. Germans detected Moon radar echo in 1943 when developing the Mammut long-range radar, at ~600 MHz. They had to keep it secret, and only in ~1950 the engineer who saw Moon echo, earned his Dipl.Ing. degree for his work.”

A German engineer and not the Project Diana team deserves the credit for being the first to bounce radar waves off the moon? Really?

A different perspective on this earlier moon contact is offered by Magnus Lindgren in his Master’s Thesis submitted in 2010 to the Chalmers University of Technology in Goteborg, Sweden, in which he notes that “operators of a German experimental radar succeeded in hearing their own lunar echoes in January 1944, by pure chance.”

There is a big difference, as Lindgren goes on to point out, between accidentally hitting the moon because it happened to get in the way when you were really trying to do something else vs making a "deliberate" (Lindgren's word), carefully planned effort to hit the moon based on antenna design and location, elaborate calculations of the moon’s location, etc, thus “determining with certainty that radio waves could penetrate the Earth’s ionosphere. This discovery,” Lindgren continues, “was a prerequisite for all space related communication projects to come, thus marking the beginning of the space age.”

Primacy is a funny thing. A lot of scientists have failed to achieve it because they asked the wrong question, or because they asked the right question at the wrong time and the technology was not there to support it, or because the vision needed to keep their objective in focus was lacking. Yes, there is always an element of luck involved, but planning, timing, and a perfect match between the goal and the resources available to achieve it are also required.

On January 10, 1946, all these criteria were met. The Project Diana team aimed their radar at the moon, hit it, and recorded the echo back on earth a little over two seconds later. Then they did it again, and again. They were the first to do this. Ever. End of story.

**************************

| "[One] evening King came home beaming and hugged Elsa, saying, 'We did it!' He wouldn’t tell me what but they were both ecstatic. Your mother’s comment was a matter-of-fact 'I knew you would.'….It was, I later learned, that they had…bounced [radar] off the moon." Patricia Lewis McManus, Elsa's niece |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed