Then, on August 11, the Norwegian vessel Bergensfjord docked at a Brooklyn NY pier. Twenty-one of those aboard - 10 passengers and 11 crew members - were ill. A team of doctors and city officials, having been warned in advance, were on hand to meet the ship and quickly sent those where were ill to nearby hospitals. The first few cases of what turned out to be one of the deadliest pandemics in human history had landed in New York City.

And a singularly unpleasant death it was. The historian Mike Wallace described “patients gasping for breath as their lungs filled with bloody frothy fluid.” Within days or even hours, they basically drowned in their own bloody fluids. Victims could awake feeling fine and be dead by midnight.

Consistent with the usual demographic pattern, children under five and adults over seventy were at elevated risk. Unlike most influenza epidemics, however, healthy young adults between the ages of 20 and 40 were also highly susceptible to infection and suffered by far the highest mortality rates, with pregnant women being at the highest risk of dying if infected. Amazingly, except for individuals over 70, older adults, the group upon which the flu usually preys most heavily, were largely spared, producing an unusual W-shaped death curve - likely because some similar but less lethal bug had struck during their childhood and conferred lingering immunity.

During the dark moments we are all living through today, it occurred to me to wonder whether the Great Influenza played any part in their decision to leave Brooklyn. Historically, even when contagion was less well understood, people realized that crowded conditions might contribute to the spread of disease and city-dwellers who could afford to do so often fled to less crowded areas when a pandemic struck.

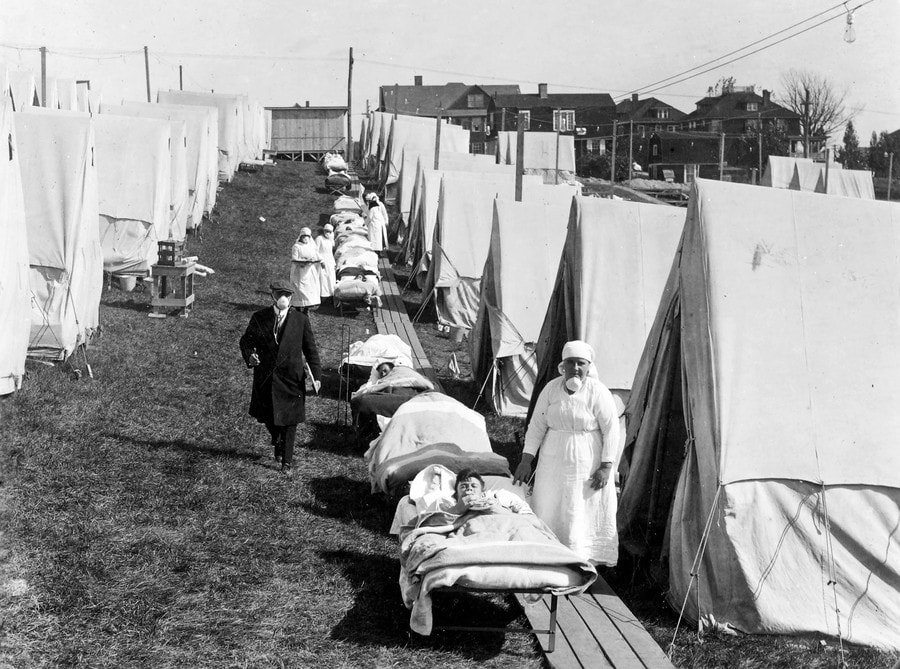

Public health officials anticipated from the start that New York would be severely affected by the Great Influenza. It was a large port city whose population had mushroomed due to recent waves of immigration. Many of its doctors were overseas fighting World War I, which at the time appeared to have no end in sight though in fact it ended rather abruptly with the Armistice on November 11 of 1918. The installation of subways and elevated trains created a brand new phenomenon, “rush hour.” New York was a center for international travel and shipping and the departure point for more than a million troops headed for battlefields in France. In short, New York was a veritable breeding ground for the flu, and Brooklyn was at its center.

If ever a family had targets painted on their backs, it was the Stodolas. Edwin was about to turn 33 and Beatrice was 28 (the modal or peak age for mortality in the 1918 pandemic), her pregnancy putting her and her unborn child in even graver danger. My father, aged three, was also in a high-risk category.

The likelihood of my grandparents having known what was coming in time to stay ahead of the fast-moving tsunami, however, is low. Front-page news focused on the Great War, while reports on the Great Influenza were buried or absent. And not just by chance; countries engaged in fighting actively suppressed news of the outbreak to avoid undermining morale. (Because Spain was not at war, the Spanish press wrote freely about it - hence the misnomer "Spanish flu.") When the approaching infection could no longer be ignored, local officials, abetted by the press, typically reassured the public either that it wasn't really the Spanish flu or that the worst was over. Not until people saw their friends, neighbors, and family members dying before their eyes, dying horribly, did they recognize the disconnect between what they were being told and reality.

If against all odds Edwin and Beatrice were somehow cognizant enough of their plight to entertain the hope that moving to a less densely populated suburban area would improve their chances of surviving the pandemic, they were quite simply mistaken. The Boston area per se was hardly a haven from the flu. In fact it struck the port of Boston even before it arrived in New York; indeed, in the end, the death rate from influenza in Boston was even higher than in New York. Nor did the suburbs provide any refuge. Except for a few communities that were either smart enough or fortunate enough to achieve true isolation from the outside world, there was nowhere to hide from the Great Influenza. In fact, there is no evidence for either Boston or New York that the suburbs fared better than more densely populated urban areas.

How did my grandparents and their children manage to survive the Great Influenza? Did they catch a milder version during the initial Spring wave, when they were in Brooklyn, that protected them from the deadlier version that came roaring back in the Fall? Did one or more of them contract the flu that raged around them shortly after they arrived in Massachusetts - but recover? Was it pure luck?

Despite my grandmother's proclivity for journaling and letter-writing, I have yet to find a word in the family archives that might shed some light on this issue. Many have likewise remarked on how little mention the Great Influenza has received, in either the history books or in literature, either contemporaneously or later. Only recently, in the wake of several other pandemics or would-be pandemics, and now in the light of the coronovirus crisis, has this lost pandemic begun to receive the scientific and historic attention it deserves.

Their seven year sojourn in Massachusetts was clearly a happy time for my father, and apparently for the whole family. Presumably it was during this period that my grandparents discovered and fell in love with Cape Cod. They eventually bought and refurbished a small cottage in Wellfleet that my grandmother christened Shining Sands, where my sisters and I spent many idyllic summer vacations during our childhood.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed