I now wish I had listened more closely.

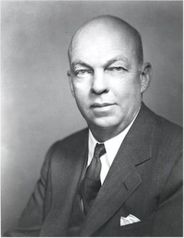

His earliest work focused on improving receiver sensitivity. While still in college, he perfected the regenerative circuit, which dramatically improved radio reception by means of a positive feedback loop in the receiver, using a triode tube recently invented by Lee De Forest. Armstrong went on to invent the superheterodyne, which still further improved reception by mixing an incoming high-frequency signal with a second tunable lower-frequency signal to produce a predetermined intermediate frequency (IF) still further improved reception. The superheterodyne outperformed every previous approach including his own regenerative receiver and remains the industry standard to this day.

He then turned his attention to developing wide-band frequency modulation (FM) radio. Radios in use at the time were designed to be sensitive to the strength or amplitude of the incoming signal (that is, amplitude modulation or AM), but were also sensitive to environmental disturbances such as thunderstorms or electromagnetic waves emanating from electronic equipment. No amount of tweaking or shielding could fix this problem. Armstrong took a radically different approach, arguing that by varying the frequency instead of the amplitude of the signal to be transmitted and designing receivers accordingly, such interference could be prevented. He devoted much of the remainder of his life to demonstrating the superiority of FM.

His first such encounter was with Lee De Forest, who responded to Armstrong’s success by laying claim to the idea of regeneration, despite little evidence that he even understood how the triode tube he invented worked, let alone that he had dreamed up Armstrong’s brilliant new application for it. The ensuing litigation lasted for over a decade, with AT&T throwing its muscle behind De Forest after buying up his patents. In the end the Supreme Court, befuddled by the technical details, ruled against Armstrong, despite universal recognition among his scientific peers that regeneration was his invention and not De Forest’s.

His conflict with De Forest, personally and professionally devastating though it was, paled in comparison to that subsequently elicited by the introduction of FM technology. By essentially eliminating the static that bedeviled AM radio, FM threatened the broadcasting industry not only by obsolescing millions of dollars worth of existing radio equipment overnight but also by diverting interest, attention, and coveted frequencies away from the anticipated Next Big Thing, television.

The Radio Corporation of America (RCA) - led by David Sarnoff, formerly his friend and collaborator, now his bitter foe - was not about to take this lying down. Both fair means and foul were employed to thwart Armstrong: Lawsuits were filed and then intentionally dragged out, patents were infringed, royalties were withheld, reverse engineering was used to buttress fake claims of priority. Armstrong was forced to remove his equipment from the top of the Empire State Building, ostensibly to make room for television equipment, driving him to move his operation to Alpine NJ. Here the first FM station, W2XMN, began broadcasting in 1939 - but only after the FCC first revoked his license and then restored it but diverted FM into a new frequency band at limited power - again, supposedly to make way for TV channel 1. (Ironically the Alpine station was briefly resuscitated after radio communication from the World Trade Center came to an abrupt halt on Nine-Eleven.)

Politically conservative and proud of his military service in World War I, Armstrong generously extended to the US government royalty-free use of the patents he had so fiercely defended - a patriotic but costly gift. Meanwhile, in addition to his legal expenses, he was self-funding much of his research at Columbia (having declined a salary for his appointment as a full professor at Columbia in order to escape administrative duties and minimize teaching responsibilities), as well as his high-powered FM station in Alpine NJ. (His red and white antenna, all 425 feet of it, still looms over the surrounding Palisades landscape, where its affluent neighbors regard it as an eyesore.)

As his debts mounted catastrophically, his attorney, Alfred McCormack, urged him to accept government contracts for his investigations of long range radar. These contracts enabled Armstrong to hire an assistant, Robert Hull, a newly-minted Columbia graduate, and together the two set about adapting FM technology to radar. The end of World War II, however, brought these explorations to a close, leaving no clear indication of what they hoped to accomplish. Since then, continuous wave FM radar has found only specialized applications, and pulse radar remains the technology of choice for most purposes.

As I worked on my most recent blog entry, about the famous bedspring antenna, I found myself becoming increasingly curious about whether Armstrong had directly interacted with the Project Diana team, and whether he had actually spent time with them at Camp Evans during this period. On the one hand, I had never, among all the first-person accounts I’d read by the Project Diana team, including my own oral history interview with my father, encountered any mention of face-to-face meetings or discussions with Armstrong. On the other hand, Belmar and Alpine are less than 100 miles apart, and Armstrong was highly familiar with the Marconi facility, where he and David Sarnoff in happier times had first listened to signals from his regenerative receiver.

The answers to these questions proved surprisingly elusive, even after I consulted such authoritative and comprehensive sources as Empire of the Air by Tom Lewis, Man of High Fidelity by Lawrence Lessing, The Invention that Changed the World, by Robert Buderi, and the librarians in charge of the Armstrong archives at Columbia University. Finally, with the help of Fred Carl, Director of the InfoAge Science History Learning Center, I found my way to Al Klase and Ray Chase, who work with the New Jersey Antique Radio Club's Radio Technology Museum at InfoAge, where they specialize respectively in the development of radar and Armstrrong's career.

Al very kindly directed me to an audio recording made in 2005 of an interview with Renville McMann, a panelist at a celebration broadcast from Alpine of the 70th anniversary of FM radio [starting at min 7:00]. In this loving reminiscence of Armstrong, McMann describes the time he innocently suggested that Armstrong point his equipment towards the moon - and with uncharacteristic vehemence, Armstrong refused. That feat, as McMann later learned, was reserved for the Army. “Armstrong had a duplicate setup of the Camp Evans equipment at Alpine,” adds Al; indeed, “the SCR-271 radar tower, sans antenna, is still there…. So clearly, there was direct contact with the Diana team. Armstrong's narrow-band receiver was crucial to the success of the project.”

Al goes on to observe, “It's easy to assume Armstrong visited Camp Evans during the Diana era, it was only a day trip, even without modern roads, but I see no hard evidence. Dave Ossman, in his excellent radio drama version of Empire of the Air [starting at min 7:26] has Armstrong at Evans for the first experiment, but rereading [the original book version of Empire of the Air by Tom Lewis, p. 298], we could attribute this to artistic license. I, too, would like to know if he was there.”

But as Ray muses, it appears that the famous radio pioneer took pains to maintain an "arm's length" relationship with the youthful Diana team to ensure that they got full credit for whatever successes they achieved. He did such a good job of covering his tracks that barring some unexpected scholarly find, the nature and extent of his personal interactions with the Project Diana team will remain shrouded in mystery.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed