So I felt more than a little sheepish when it only recently crossed my mind that my childhood pediatrician, Dr Helen E Jones, was a part of that history; and that even being her patient, at a time when only a tiny fraction of physicians were women, was an unlikely feature of my childhood. I immediately recognized this topic as a potential blog entry. Almost as immediately, I recognized that despite my vivid visceral memories of Dr. Jones - her strawberry blonde curls, her small physique, her all-business demeanor, and of course all those injections! - I knew next to nothing about the biographical details of her life or the hardships she must have endured to obtain her credentials and establish a thriving medical practice in a small coastal New Jersey town.

Having gotten as far as I could with google and the archives of the Asbury Park Press, I consulted two main additional sources. One was my friend Sandra Chaff, Archivist-Director of the MCP Archives and Special Collections on Women and Medicine at the time I worked on the oral history project, who was fierce about finding and preserving documents, photographs, and artifacts relating to the history of women physicians. The other was a Facebook Shark River Hills nostalgia site several of whose members were also patients of Dr Jones and were generous in sharing their recollections.

I am now happy to report that with a little help from my friends (thanks, guys!), I have cobbled together at least a blogs-worth of information about the elusive Dr Jones. And I am especially happy to post it on February 3, National Women Physicians Day, celebrated on the birthday of Elizabeth Blackwell, the first woman to graduate from medical school in the US and a trailblazer in promoting medical education for women throughout her life.

After her graduation from Asbury Park High School, wishing to see more of the country, she enrolled in premedical studies at the University of Michigan. She also joined the Psychology and German clubs during her days in Ann Arbor and pursued music and dramatics as well. During her summers at the Jersey Shore she worked as an assistant at a first aid station at the beach.

In September of 1940 she enrolled in Temple University School of Medicine - one of around 10 women in a class of 104. “Gone are the carefree college days,” intoned Dr John B Roxby in his welcoming speech. “You have chosen a great but difficult path, and the travail which lies ahead is of a quantity which may defy your present imagination.” Along with the demands described by Dr Roxby, additional clouds hung on the horizon. The prospect of American entry into World War II loomed larger every day and became a reality at the end of 1941, with the bombing of Pearl Harbor. The Wagner-Murray-Dingell bill of 1943 was as unsuccessful as succeeding socialized medicine proposals but nonetheless caused uneasiness and fear of the unknown.

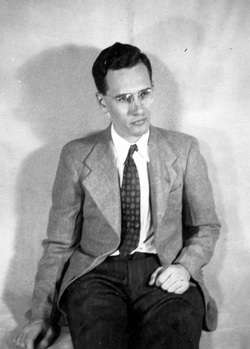

Skull (Temple Medical School yearbook), Dec, 1943, Helen E Jones.

Skull (Temple Medical School yearbook), Dec, 1943, Helen E Jones. During the latter half of her senior year she interned at the Chestnut Hill Hospital in Philadelphia. Following graduation she interned at the Jersey City Medical Center.

At the end of 1944, she started posting notices in the Asbury Park Press that her offices at 617 7th Avenue, located in her home in Asbury Park, would open for business on January 2, 1945, with office hours 2-4 and 7-9pm, and on Sundays by appointment.

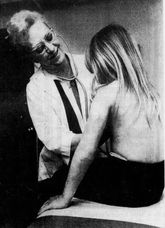

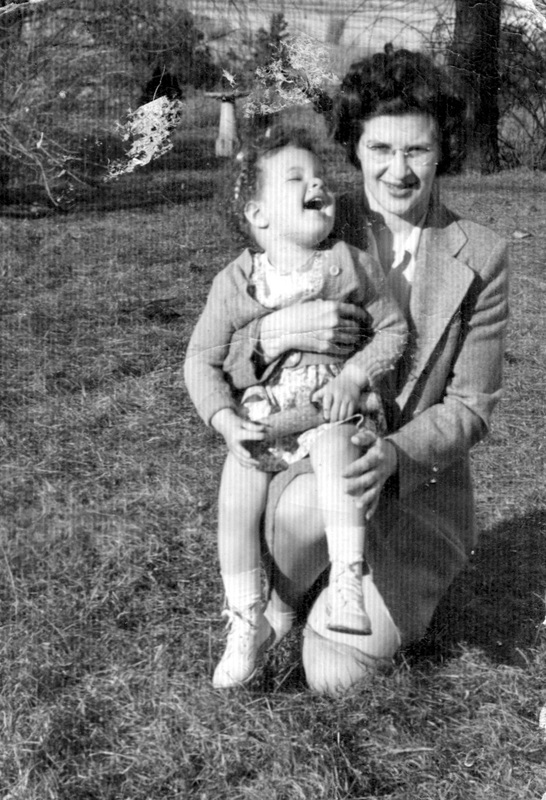

Asbury Park Press, 0ct 11 1954. This photo shows Dr Jones (center, holding baby) exactly as I remember her.

Asbury Park Press, 0ct 11 1954. This photo shows Dr Jones (center, holding baby) exactly as I remember her.  Asbury Park Press, Apr 30, 1974, shortly before her retirement.

Asbury Park Press, Apr 30, 1974, shortly before her retirement. Dr Jagdish Bharara took over her practice in New Jersey, and Helen sold her house in Deal Park.

On May 19, 1974, Helen began her new 40-hours-a-week “day job,” which involved working with what were then described as “retarded and emotionally disturbed children” at Camarillo State Hospital. At the time she arrived, Dr Ivor Lovaas, a pioneer in the application of behavior analytic techniques to autistic children, was at the peak of his career at Camarillo State, so whether or not she worked with him directly, it is impossible that she wasn’t touched by his somewhat controversial use of both rewards and punishments to encourage language skills and reduce self-injurious behavior. It would be interesting to know what she thought of his research-oriented approach, in contrast to the treatment model that had guided her own career.

Helen Elizabeth Jones died on December 17, 1993 in El Dorado, Placerville, California, at the age of 75. Four years later Camarillo State Hospital permanently shuttered its doors.

Although I was too wimpy to engage in such hijinks, I had my own personal nickname for Dr. Jones that still comes more naturally to my tongue than her given name: “Fanny Jones” (yes, for the obvious reason). If you think you detect an undertone of affection in that sobriquet, you would be quite wrong. And yet she never did me any harm; indeed, she probably saved my life on more than one occasion. The only thing I can say in extenuation of my youthful animus is that I remember her as rather severe, so the pain she inflicted was not much tempered by warmth or playfulness.

No one likes having a shot, but I cannot remember this level of needle-phobia in the days when I took my own daughters to the doctor. Did we have to endure more shots in those days? I may be exaggerating but I can’t remember a visit to Dr Jones that didn’t include at least one shot. Although the number of vaccine-preventable diseases is larger today than when I was a child, combinations such as diphtheria-pertussis-tetanus didn’t come into use until 1948; the shots and their boosters were given separately. Smallpox inoculations continued to be administered (remnants of my scar are still visible) until the late 1960s and beyond, even after the disease had been eradicated worldwide. The long-awaited vaccine that finally ended the terrors of polio became available in 1955, but the orally-administered version didn’t make its appearance until 1961. So - for awhile, yet another shot.

Non-routine shots were also commonplace - for example, tetanus boosters after injuries, such as I received after a dog bite when I was ten. (Telltale marks where Dr Jones cauterized the wounds can still be seen on my chin and neck - more battle scars!)

Although the antibacterial properties of the Penicillium fungus had been recognized for decades by the time the Scottish biologist Sir Alexander Fleming succeeded in culturing and concentrating it in 1928, it wasn’t until World War II that a form stable enough to be mass produced for clinical use was developed. Overuse of this miracle drug probably began almost immediately. I became seriously ill with bronchitis and pneumonia when I was in the first grade and Dr Jones arrived at our home every morning for two whole weeks (yes, Dr Jones made house calls!), clutching her black doctor’s satchel, to give me an injection. More than my fair share - so little wonder, perhaps, that I felt traumatized by my encounters with her!

Alternatively, is it possible that shots actually hurt more back then? Just about around the time I began my career as a pediatric patient, glass syringes with interchangeable parts, already a staple of medical practice, began to be mass-produced. Not until the mid-1950s were disposable plastic syringes introduced, eliminating the problem of contamination from improper sterilization; might they also have had a smoother action that reduced the ouch-factor? Or do newer manufacturing techniques produce finer and sharper needles than were available in the 1940s? Does modern medical training focus more on minimizing or distracting from the pain of injections? Just spinning out ideas here, but descriptions by diabetics of changes in insulin injections over time lend credence to the possibility that shots are less painful now than they used to be.

By the time Helen graduated from medical school, to be sure, these patterns were starting to crack a little. As a result of World War II, women were working outside the home in larger numbers, a trend that undoubtedly helped Helen build her practice. Helen was also fortunate in having as a role model a mother who ran her own business at a high professional level. Nonetheless, Helen played it safe, opting for a “soft” specialty and remaining single. Failure was probably not an option,

This is not in any way to imply that her choice of pediatrics was simply a matter of expediency. "Medicine is demanding,” she said, “but the thing that makes it all worthwhile is seeing a child grow up well and happy…. You become close to the children and they're almost like your own." She maintained a deep conviction of the larger importance of her work: "They will be the heads of state, one way or the other. You look at a little baby and realize that everybody who comes in contact with that child is going to have an influence on the development of his personality and character.”

Devoted as she was to her profession, Helen was not completely devoid of outside interests and activities. One of my Facebook “informants,” whose cousin worked for many years as Dr Jones’s receptionist, said that Dr Jones shared her home in Deal Park with her sister and brother-in-law, which afforded some presumably welcome companionship. Her mother’s daughter, she was an accomplished musician who played piano and organ. Other hobbies included collecting stamps, with an emphasis on those featuring opera and the history musical instruments; and caring for her two Yorkshire Terrier stud dogs, one of which took a first at the Westminster Dog Show in Madison Square Garden.

Did Helen’s busy pediatric practice - stampeding kids and all - add up to a full and rewarding professional life? Did her hobbies enrich her nonworking hours? Did she miss having children of her own or did she enjoy a little calm and quiet when she returned home in the evening? Did she indulge herself in a few precious moments at the piano communing with Chopin, or did she just drop into bed exhausted? Did her second career working with special-needs children and scaling back to a 40-hour work week in an easier climate give her a new lease on life?

I wonder.

I offer this blog entry not as a love letter, exactly, but as an expression of gratitude for the medical care I was fortunate to receive as a child and as an apology for the ill will I harbored against Dr Jones for no other reason than that she always seemed to be brandishing a needle.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed