This charming anecdote about my father sharing his elation with my mother was told to me by my cousin Tricia, who was twelve years my senior and lived with my family off and on at several points during my childhood.

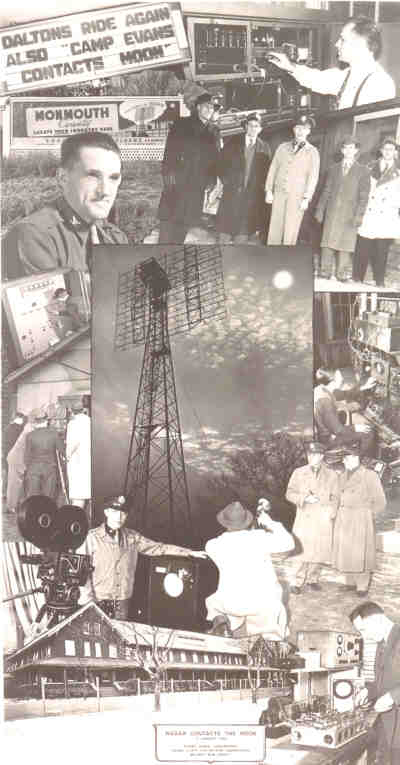

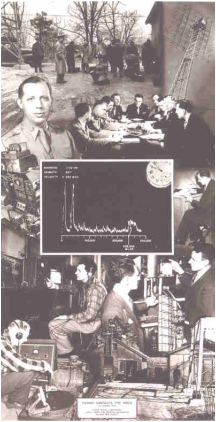

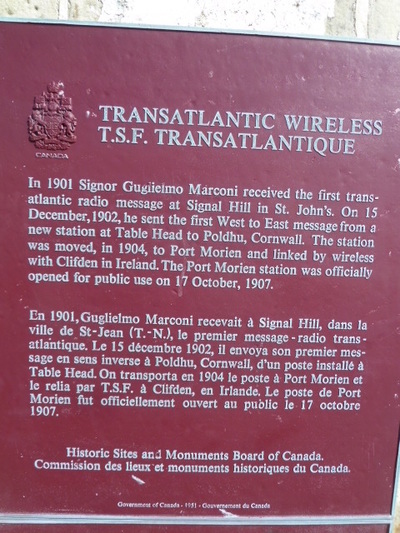

So success had crowned their efforts, and the tiny band of volunteers at the Evans Signal Laboratory had scooped much bigger labs at home and abroad. The news that our horizons were no longer limited by the earth’s atmosphere, and that communication with extraterrestrial bodies was now possible, made front page headlines all over the world, followed shortly by newsreels shown before the Saturday matinee and extended radio interviews. My father even received warning letters about “disturbing God’s back yard” - a sure sign that a significant scientific advance had been made.

Not exactly.

In fact, although the successful moon bounce occurred on January 10, 1946, the Army actually sat on this news for more than two weeks before finally revealing it to the world on January 25. Some of the delay was undoubtedly dictated by a desire to have outside experts review the team’s claims, but an abundance of caution cannot entirely account for the aura of reticence surrounding the event. Very little information was initially revealed about even the five principals, who were described in the first NY Times article about the feat as "modest in the extreme. Only at the reporters' insistence was there any revelation of biographical material on the quintet." According to the late David Mofenson, son of team member Jack Mofenson, “My father used to like to quote Lincoln's Gettysburg Address: ‘the world will little note nor long remember….’”

So why was the Army so reluctant to exercise its bragging rights? Perhaps its pride in Project Diana was tempered by a lingering concern that too much had been revealed about their capabilities (which just a few months earlier might have resulted in Camp Evans being a target for German or Japanese bombs). Or possibly Jack DeWitt, though not actively deceptive, had not been as forthcoming about what he was up to as the Army higher-ups might have wished, as the following passage from an oral history interview I conducted with my father in 1979 seems to imply:

“[Jack DeWitt] had thought for a long time about the possibility of getting enough energy onto the moon to be detectable back on the earth, and with this cadre of people that I was heading and the various pieces of apparatus that were around, we did some thinking about it and decided we had the resources to do the trick, so pretty much on a slave labor basis, we started to work on this moon radar project, and a lot of other people got "scrounged" into it. And to make a long story short, the thing came off successfully. Then we let our bosses know what was going on….”

The Army’s reluctance to take credit for Project Diana didn’t end there. Decades later my father, then in a high-level position in Electronic Warfare at the Pentagon and lobbying for a 40-year anniversary celebration of Project Diana (which he always regarded as his life’s proudest achievement), was unable to get sufficient security clearance to gain access to records of his own work. The 40th anniversary passed with barely a ripple.

David Mofenson told me he later tried to get the US Post Office to issue a stamp commemorating the 50-year anniversary: “I wrote our U.S. Senators etc but could generate no interest - more important to put out stamps celebrating Daffy Duck, Bugs Bunny!” (Previous stamps have featured the lunar landing, and David might have been pleased to know that on February 22, 2016, the USPS issued a $1.20 Forever stamp showing a beautiful photograph of the full moon. So far no mention of Project Diana, though.)

The 70-year anniversary of Project Diana took place on January 10 of this year. For ham radio operators and Earth-Moon-Earth enthusiasts, and for historians of space exploration, Project Diana is still sort of a big deal. The InfoAge Science History Museum, which has been heroic in staving off the Army’s efforts to dismantle the Project Diana site, hosted a gala event in which museum volunteers, the Ocean Monmouth Amateur Radio Club (OMARC), and Princeton University, reenacted this historic milestone. So far as I know, however, the Army remained on the sidelines, leaving others to commemorate the event.

75th anniversary, anyone?

RSS Feed

RSS Feed