With great honor comes great responsibility! In particular, I find myself heir to most though probably not all of the Stodola family archives. This material did not come to me all at once, but piecemeal over the course of many decades. I can't even remember how it all made its way to me. Some of it I've had as long as I can remember. Some my father packed away in cardboard cartons when we moved from New Jersey to New York. Once my mother died, he never again opened them or made any attempt to sort their contents. Later the boxes, still unopened, were carted from our basement on Long Island to a storage unit in Florida. My stepmother tried valiantly over time to identify and get things into the hands of the right Stodola child (mostly me, because she knew I would care and share), But like me, she was hampered by cryptic labels (my favorite: "him and me") and nonexistent dates, and in addition knew far less about our family history than I.

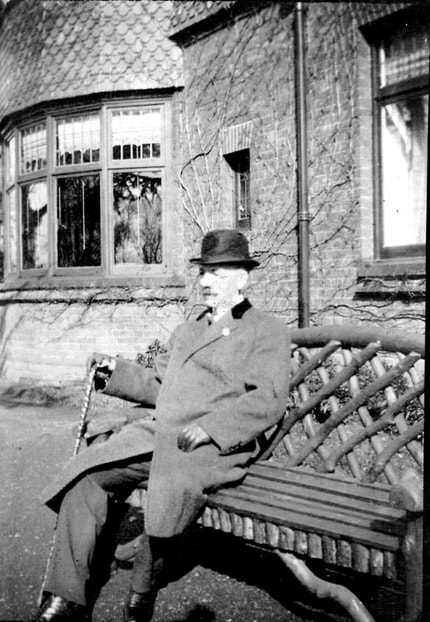

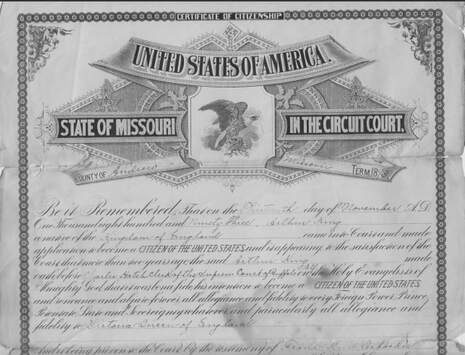

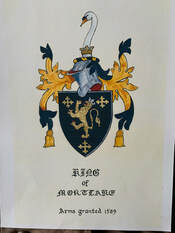

Although I have eight great grandparents and sixteen great great grandparents, just like everyone else, the Kings have always seemed a little larger than life to me because I heard so much about them from my grandmother, who as an adored only child maintained close ties with her father’s relatives in England; and because the Kings were a prolific and retentive lot, leaving a rather large paper burden behind for their descendants to sift through. Over the years, I have threaded my way through most of the documents in my possession and succeeded in identifying many though not all of the photos. I have also connected, through DNA matching and more traditional methods, with second and third cousins who still live in the UK and are much more steeped in King history than I.

I vowed on the spot that we would one day make a similar pilgrimage to Little Glemham.

“One day” finally arrived more than 20 years later, this past April, when we embarked on a two week tour of London and environs that included an exploration of Little Glemham in Suffolk and a visit with two second-cousins-once-removed in Sussex. Except for the stress of driving on the left, along narrow roads with many roundabouts, which fell solely upon Ovide, and the stress of navigating, which was my bailiwick, our vacation could only be described as idyllic. Even the weather cooperated - we never even unpacked our umbrellas.

The rest of this essay is about our trip to the UK.

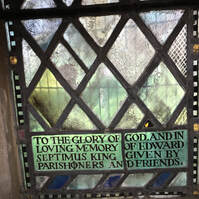

When we started planning our itinerary, we realized we could include Easter in our schedule, which seemed a propitious time to visit St. Andrew’s. I emailed the current rector, who assured me that although St Andrew’s is now part of a “benefice” of eight churches - necessary because attendance had dwindled too much to justify weekly services at each church - an Easter service was indeed planned for St. Andrew’s.

On our first full day in East Anglia, knowing we might not have an opportunity to poke around much on Easter Day, we stopped by St. Andrew’s, which looked exactly as I remembered it in my photographs. The only problem was, it also looked like every other church in every other nearby village, even to the little gatehouse in front, with only minor variations in size and layout. These parish churches date back to the Middle Ages - starting life as Roman Catholic churches and after Henry VIII becoming Anglican - and I guess having hit on a successful formula, the builders decided to stay with it.

The house was built by the DeGlemham family in the mid 16th century, replacing the moated manor house their forebears had built on the site in the 13th century. In 1709 the North family purchased the property, along with the lordship of the manor, and shortly thereafter made major structural changes to give it the beautiful Georgian facade it boasts today. During the latter half of the 19th century, when my great great grandfather was rector of St Andrew’s, the mansion was occupied by Alexander George Dickson, a Conservative Member of Parliament and second husband of the widow of Lord North.

Think Upstairs Downstairs. Think Downton Abbey. Think (as did I) of the rector of St Andrew’s being honored by an occasional invitation to tea at Glemham Hall.

During the Battle of Britain in 1940, their resources stretched almost to the breaking point, the British sent a delegation to the United States to propose a marriage of British science and knowhow with American industrial capability. Public sentiment in America favored neutrality; Henry Tizard, head of the mission, took the bold step of showing the Americans the technical innovations they had achieved without any promise of reciprocation. As Tizard hoped, the sheer impact of British superiority in the development of radar was sufficient to convince the Americans it was in their own best interest to support the British effort, and thus began the amazingly productive British-American collaboration in the development of radar.

It was just around this time that my father left his entry-level job at the War Department assigning radio frequencies to Army facilities ("boring!") to begin his fledgling career as a radar scientist. Although the Tizard Commission visited Bell Labs in New Jersey and Columbia University in New York City, I have found no evidence of their having stopped in Belmar - and in fact the subsequent locus of collaboration focused on the creation and development of the famous Rad Lab at MIT rather than on work already in progress by the Army Signal Corps at Camp Evans. Still, it seems likely the American commitment to the British war effort, cemented by the Tizard Commission, set the stage for my father’s career in radar research and his particular expertise in moving target detection.

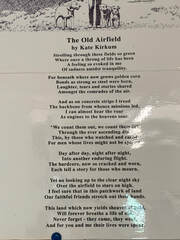

Although we didn't have a chance to visit the Bawdsey Radar Museum, we did spend a couple of engrossing hours at the Parham Airfield Museum near Little Glemham, housed in the original World War II Control Tower of Framlingham Air Force Station #153. The museum is dedicated to the 390th Bombardment Group, which carried out more than 300 combat missions in the Boeing B17 “Flying Fortress,” during which 19,000 tons of bombs were dropped and 342 enemy aircraft were downed. Nearly 200 American planes never returned, and today being Memorial Day, it seems especially fitting to honor the more than 700 service members killed in these risky missions. Also worthy of mention are the humanitarian flights undertaken just before V-E Day to supply desperately-needed food to the Dutch.

In a world where Americans aren’t universally welcomed or appreciated, it was heart-warming to bask in the affection and gratitude with which the Yanks are still, even after all these decades, remembered at Parham.

Cousin Jane introduced me to her cousin (and like Jane, my second-cousin-once-removed), Ian, and we enjoyed a delightful luncheon with him and his wife Nathalie. Ian, unlike me, is a bona fide genealogist, so it was gratifying to be able to help him fill in the blanks on Arthur’s family (including five generations of descendants with the middle name of King).

Of all the things he shared with me, nothing was more thrilling than his photos of the Boys’ Butterfly Collection. One of the few pieces of information I could coax from my father about his relationship with his grandparents was his fond memory of butterfly collecting expeditions with Arthur. Thanks to Cousin Ian, I now understand that this activity was not just an idiosyncratic passion of Arthur's, it was part of a King family tradition that he must have hoped my father would enjoy and carry on.

In Little Glemham it was possible to walk where my ancestors had walked because the landscape has retained its small-village character and hasn’t changed beyond recognition. Probably Mortlake would have been more of a challenge.

At any rate, a quest for another day.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed