MILITARY USES

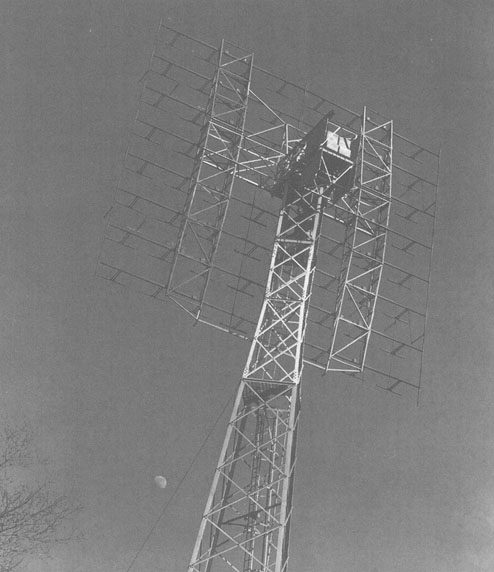

In a very real sense, Project Diana was the opening salvo in the Cold War. Concerned that the Soviets had captured enough German expertise to build missiles capable of reaching the US, the Pentagon ordered Jack DeWitt, head of the Evans Lab, to develop radar systems capable of detecting and tracking such missiles. DeWitt interpreted his mandate broadly. Since there were in fact no such missiles in existence on which to perform such a test, he found in this directive the perfect excuse for pursuing his decades-old dream of “shooting the Moon.” “Well, if we could hit the moon with radar,” he argued, “we could probably detect the rockets.” With almost anyone else at the helm of Camp Evans, the project might have taken a different and probably less informative turn. Indeed, the successful moon shot appears to have taken DeWitt’s superiors by surprise, and two weeks of checking and replicating elapsed before the War Department allowed the achievement to be announced to the world.

Although radar had proved highly effective in detecting enemy ships and aircraft during World War II, many doubted that radio waves could penetrate the ionosphere, bounce off a target, and be detected back on Earth. Project Diana served notice that anything the USSR wanted to throw at us, including intercontinental ballistic missiles, could be detected and tracked as well. Development of weapons to intercept such missiles followed; the arms race and the quest for mutually assured destruction was underway.

SCIENTIFIC IMPLICATIONS

Robert Buderi, in his book The Invention that Changed the World, about the central role of the MIT Rad Lab in the development of radar (for which the Signal Corps’ coup in bouncing radar waves off the moon constituted a bit of an inconvenient truth), dismisses the achievement as little more than a clever demonstration: “The hullabaloo soon died down. For all its remarkability as an engineering feat, the DeWitt experiment held next to nothing of scientific interest.”

Is this really so? True, Project Diana was not an experiment or discovery in the same sense as was, say, unraveling the mystery of DNA. Still, it provided conclusive nonsupport for the going hypothesis that the ionosphere could not be penetrated by radar, and by doing so it lifted a veil in the field of astronomy. For most of human history our knowledge of the universe was based solely on the visible portion of the electromagnetic spectrum. Adding the radio band to our toolbox extended our observational capabilities tenfold. It also enabled not only passive observation of but also active communication with the universe beyond.

Once the War Department conceded that Project Diana had really accomplished what Jack DeWitt claimed, it was quick to grasp the potential of moon bounce technology. Among its predictions: accurate topographical mapping of heavenly bodies, measurement and analysis of the ionosphere, and radio control of space travel, missiles, and orbiting artificial satellites. The news media also chimed in, with Time suggesting that Project Diana might provide a test of Einstein’s theory of relativity, while a more skeptical Newsweek article labeled the War Department’s predictions “worthy of Jules Verne.” As a NASA historian concluded years later, “all of the predictions made by the War Department, including the relativity test, have come true in the manner of a Jules Verne novel."

ADVANCES IN COMMUNICATION

Project Diana touches our lives every time we pull out our cell phones, the most ubiquitous example of satellite communications. Personal mobile communications devices have changed our lives and our expectations in ways ranging from how we deal with emergencies to the level of "sharing" we now expect from each other. (How many stories have you read and movies have you watched turning on plot twists that would not be possible had the protagonists had cell phones?) In many parts of the developing world cell phone technology is the open sesame to global participation. It does not replace land lines, it replaces nothing. It is all there ever was.

Project Diana is also the locus classicus for Earth-Moon-Earth communication, whereby amateur radio operators interact with other hams around the world by bouncing radio signals off the moon. My father and his team hoped to receive echoes from their own transmissions, whereas EME enthusiasts are more interested in sending out signals and having them received elsewhere on earth. But the technology is conceptually identical, and presumably so is the joy experienced by my father in being able to use the moon as a relay station for radio signals.

HELPING TO SHAPE THE AMERICAN MYTH

Would the advances described above have happened without Project Diana? In some form, almost certainly yes. Several other labs were poised to mount similar demonstrations, and within a month of Project Diana’s spectacular triumph, Zoltan Bay of Hungary, adopting a different approach from that used by the Camp Evans team, also successfully “shot the moon.”

But Bay was second, and Project Diana was first, a fact that had a profound impact on the American psyche. Coming as it did on the heels of America’s contribution to the defeat of the Axis powers in World War II, based on our “can do” spirit and technological expertise, it was so to speak the frosting on the cake, suggesting a host of peaceful as well as military applications for our capabilities. Since previous moon bounce efforts (including our own) had failed, and since many reputable scientists believed the ionosphere could not be penetrated by radio waves, Project Diana burnished our self-image as a people who could do the impossible. Because the team basically improvised using materials already on hand, it reinforced our faith in our talent as engineers and tinkerers. Finally, it provided a cultural template for subsequent American space exploration, initiating the tradition of naming such projects after ancient Greek and Roman gods like Mercury and Apollo and glorifying (in the person of Jack DeWitt) the cowboy hero with the “right stuff” later exemplified by American astronauts.

Every country creates a mythology about itself that helps to form its national identity and make its people feel as though they are part of something larger than themselves. What aligns with the mythology is selected; what doesn't tends to be winnowed out. The postwar years were a time when America was starting to flex its muscles on a global scale, and its sense of itself was rapidly evolving to accommodate these developments. Project Diana was perfectly poised to be part of this process. For a variety of reasons, it is not so easy these days to feel exceptional on the global stage, which is probably why so many Americans harbor nostalgia for what in retrospect seem to have been simpler, better times.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed