Marconi showed an early interest in and aptitude for electronics, sending a wireless message from his bedroom to his mother's garden at the age of sixteen. Fortunately for him, his parents had both the inclination and wealth to support his talents. In his early twenties, failing to generate much interest in his work in his native Italy, he relocated to England and also spent much time in America, combing the coasts of both continents for spots suited to transatlantic radio communication, and leaving many wireless telegraph stations in his wake.

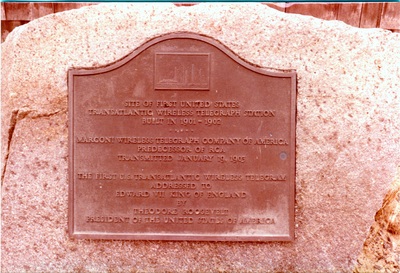

Among Marconi’s hand-picked sites was the Belmar Marconi receiving station, located on a hilltop on the south bank of the Shark River Basin, at what later became Camp Evans, home of Project Diana and a stone's throw from my childhood home in Shark River Hills. The original buildings were constructed between 1912 and 1914 by the JG White Engineering Corporation for the Marconi Wireless Telegraph Company of America as part of Marconi’s “World Encircling Wireless Girdle” project. Weak transatlantic signals received at the Belmar Station were then relayed via a landline connection to a high-power transmitting station in New Brunswick, 32 miles to the northwest.

In 1913 Marconi returned to his native Italy, where he and his wife became part of Rome society and he was made a member of the Italian Senate. During World War II he was placed in charge of the Italian military’s radio services. Sadly but perhaps inevitably, Marconi later in life joined the Italian Fascist party and became an active defender of its ideology.

Today we honor him not for his politics but for his work as a visionary who, ahead of his time, dreamed of a connected world and dedicated his life to making his dream come true - an accomplishment for which he shared the Nobel Prize for Physics in 1909.

* * * * * * * * * *

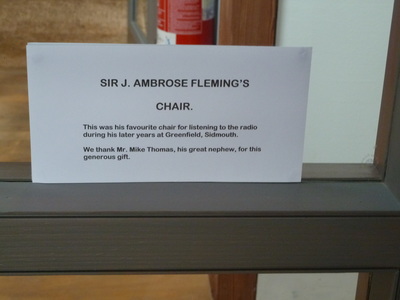

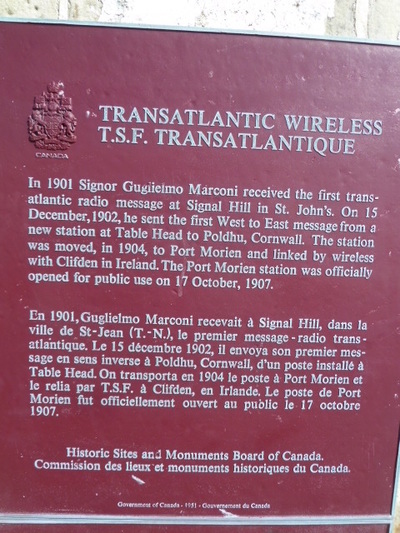

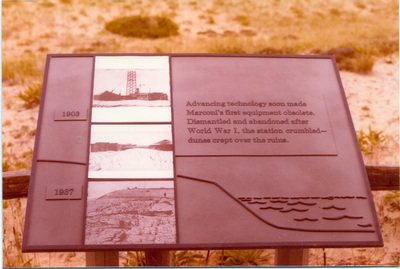

Several decades ago my husband (call sign K8EV) and I had to cut short our delightful meanderings in southern England at the Devonshire-Cornwall border in order to keep an appointment with some friends in the Lake District. In 2010, we jumped at a chance to pick up where we left off and spent the better part of a fortnight exploring Cornwall. An unlikely (to me) highlight of our tour was a visit to the Marconi Centre in Poldhu, site of the Poldhu Wireless Station, where Marconi claimed (somewhat controversially) to have transmitted the first east-to-west transatlantic radio message in December, 1901, to his station on Signal Hill, St. John's, Newfoundland. The Poldhu station was built partly on enclosed pastures that remain to this day, making it hard to keep antennas in working order because the cows apparently have a taste for coaxial cable. The original station was designed by John Ambrose Fleming, who invented the ancestor of all vacuum tubes, earning him the sobriquet "father of modern electronics."

That station was decommissioned in 1934 and demolished in 1937, but six acres were given to the National Trust in 1937 and more land added in 1960. The Marconi Centre, built in 2001, houses a Marconi museum and also provides meeting space for the Poldhu Amateur Radio Club, GB2GM. It took a little persistence to find the site but we ended up spending a fine afternoon perusing the museum's fascinating exhibits and chatting with the local hams.

It’s what hams do.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed