Perhaps this is why I've never minded machines that beep at me.

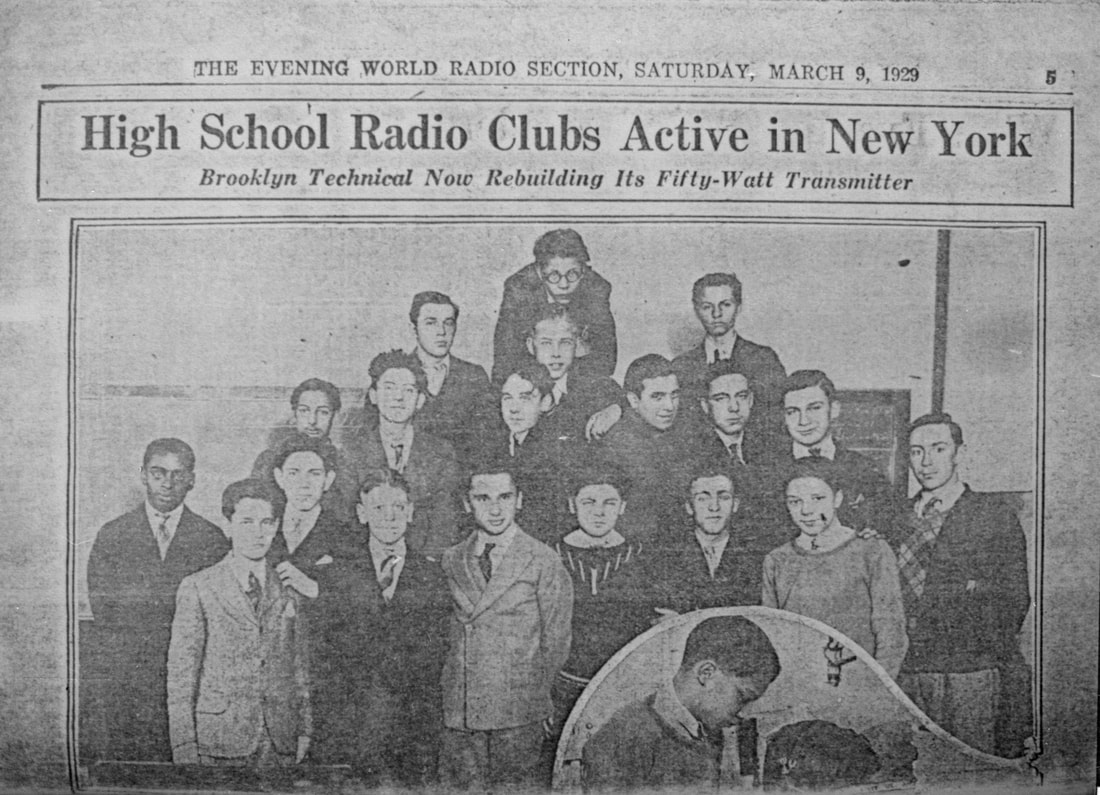

But in the distinctive form we know today, ham radio dates back to the first decade of the twentieth century. It was then that the relevant equipment and components became commercially available (1904), the first magazine aimed at encouraging amateur radio and “home-brew” equipment, Modern Electrics, was launched (1908), the first amateur radio club, The Junior Wireless Club, Limited, of New York City, was formed (1909), and call letters or call signs came into use (1909). It was also then that the curious term “ham” entered the vocabulary - probably as a pejorative. as in "ham-fisted amateur", but it was eventually embraced by skilled operators who knew that the correct opposite of “amateur” was not “professional” but “commercial”; hams were doing it for love, not money.

Note that although in those early days (and even in my own childhood) Morse code was almost synonymous with ham radio, voice communication was also possible almost from the beginning.

In 1910 a bill introduced in the Senate to prohibit “amateur experimenting” was roundly defeated thanks to the lobbying efforts of the Junior Wireless Club. (A similar effort in 1919 to limit wireless communication to the Navy and exclude amateurs altogether was also quashed.) The succeeding decade saw the introduction of licensing (1912), frequency restrictions and operating instructions (driven in part by the shocking sinking of the Titanic in 1912), the regularization of call signs (1913), and the proliferation of ham jargon (boatanchor, ragchew), as well as CQ (“seek you” - an early version of texting shorthand) and the Q signs (QRZ [who are you?], QSO [did you hear me?], and dozens of other abbreviations that facilitated rapid coding). QSL cards confirming a contact, often quite creative and artistic, were first used in 1916 and became more standardized in content (sending and receiving call signs, date, time, frequency, mode of transmission, and signal report) in 1919.

All amateur radio activity was forbidden during World War I but sprang back when the War ended. By 1920 there were around 6,000 licensed hams including a handful of women (officially dubbed "YL" - Young Ladies - by the American Radio Relay League in 1920; yes, really). In 1923, following assignment to the "useless" higher (short-wave) frequencies by the government, amateur radio operators accomplished the “impossible” - dependable wireless communication between the US and Europe using relatively low power. DX - hamspeak for sending messages over long distances - had truly been achieved.

Any opportunities my father and his colleagues might have had for pursuing or sharing this interest during their years with the Signal Corps, however, were cut off a month after the attack on Pearl Harbor, when as in World War I, all ham radio licenses were suspended to prevent spying. (An exception was made for VHF operations on 112 MHz by around 250 hams who were part of the War Emergency Radio Service.) Because of a clash over postwar frequency allocations - mainly between radio titans Armstrong (FM Broadcasting) and Sarnoff (RCA/NBC TV), but also threatening access by amateur radio (represented by ARRL) - US hams were not allowed back on the air until November of 1945.

The amateur radio community has participated in and benefited from satellite technology as well, in the form of satellites built by and for the amateur radio community, starting with OSCAR I (Orbiting Satellite Carrying Amateur Radio) in 1961 and continued by AMSAT, an umbrella designation for amateur radio satellite organizations all over the world. AMSAT launched its first satellite in 1970; its most recent satellite was put into orbit in 2018.

In the 1970s, CB started to fill the niche that had been occupied by ham radio in my father's life, and call sign "W2AXO mobile" was joined if not replaced by his CB handle "Road King." By then he was living in Florida, and CB was in its heyday. Because CB had no licensing requirements, it offered a larger if less selective field of prospective contacts and a built-in conversation topic of mutual interest to nearby drivers (though as Bob remarked, it's impossible to imagine our dad saying, "Hey, good buddy, there’s a smoky near exit 5...”). He had also started using a computer by this time, and I don't think he ever again set up a station in his home.

Nevertheless, among the questions that pop up upon googling relate to the relevance of ham radio in an age of digital technology, whether it can survive, and even does it still exist? That last one is easy - yes, it definitely still exists. ARRL still registers over 3/4 million licensed hams in the US, with over two million more worldwide. Facebook groups on ham and amateur radio have many tens of thousands of members who contribute hundreds of posts per day.

Questions about the future and relevance of ham radio are more problematical. After all, many of the things that today’s older hams could do when they were young that seemed so magical at the time - phone calls around the world! free! - can now be done using cell phones, no training or license required.

Does ham radio have a future? Despite the healthy census of licensed hams, many are admittedly getting long of tooth, and efforts to recruit younger members via field days, Scout merit badges, or connecting them with “Elmers” (mentors) typically yield only a few new enthusiasts, and even those often fall away after the initial excitement fades.

Is this really a legitimate worry? One ham, after browsing through amateur radio magazines of the 1940's and 1950's, commented on complaints about the lack of youngsters taking up the hobby: "It seems to have been a 'new' problem for a long time." To be sure, it is the kind of activity that will always have a specialized and limited audience - STEM types who also like activities with a hands-on component - but isn't that also part of its appeal?

If the goal of recruitment is to enable the hobby to continue unchanged, frozen in amber, it is almost certainly doomed. If on the other hand the activity is encouraged to evolve, while retaining its central focus on electromagnetic theory and communications - and on engineering new and clever ways to bring them together - then there is less reason for despair. Tell them that the new software-defined radios (SDRs) have enhanced signal processing and detection capabilities for both receivers and transmitters, bringing ham radio fully into the computer age. Tell them they don't need a pricy transceiver, that low-cost "hand-helds," in conjunction with repeaters that pick up weak signals and amplify them to extend their reach, will let them make contact and join networks on the go. Tell them about AMSAT and point out that Elon Musk isn't the only one who can send communications satellites into space. Tell them that almost all astronauts have ham licenses so that they can educate classroom and museum groups about their mission, or just call home, while circling the globe.

Worries that children will give up hamming when they discover cars and sex strike me as misplaced. Isn't that often the way with childhood interests? I gave up piano lessons when I was fourteen, over my parents' protests, but have returned to music again and again at various times in my life and am grateful for the pleasure it has brought me over the years. And my husband Ovide, who was licensed in his teens only to stop altogether during his career-building years (though he credits the basic electronic knowledge he acquired as a ham with enabling him to set up his lab), resumed and greatly upscaled his ham activity after retirement. (See below for the long version.)

And why limit recruitment to kids? It's a hobby that can be taken up and enjoyed anytime in life. Women in particular, who might have missed out on amateur radio as children because it seemed to be so exclusively a boy-thing, would seem to represent an obvious target for recruitment (preferably with an updated vocabulary in which women hams are hams, not YLs!) and might even bring some fresh new perspectives to the field.

What better time to promote a "nerd-magnet" than when Silicon Valley is "cool"? What better time to drum up interest in a new hobby, one you can work on alone if necessary, than in the midst of a pandemic?

Is ham radio relevant in the age of cell phones and social media? If you're looking for meaningful communication with your fellow humans, try random dialing your cell phone and see what that gets you. Or try having an in-depth conversation on Twitter. And yet hams calling CQ can readily connect with technologically sophisticated people all over the world.

The answer most often offered, however, is the importance of ham radio to civil defense. When faced with a disaster, we rely heavily on a complex network of cell towers that could fail or become overloaded under extreme adverse conditions. Amateur radio, operating independently of this fragile infrastructure, can be counted on - as hams like to say - "when all else fails." This was the rationale for the War Emergency Radio Service (WERS) during World War II, as noted, and for the formation of Radio Amateur Civil Emergency Service (RACES) in 1952, developed within government agencies as a volunteer public service to maintain communications in times of extraordinary need. ARRL also maintains its own civil defense unit, called the Amateur Radio Emergency Service (ARES).

Arguably, the need to produce new generations of people with the skills required to respond in times of crisis is in itself a reason for attracting young people to the hobby. Tell them it's their chance to be a genuine superhero!

Though “when all else fails” usually refers to a breakdown of infrastructure due to weather, war, earthquake, or other major emergencies, a less dramatic instance of ham radio being the available technology occurred in my own family in 1962 when my sister Leslie spent the summer as an exchange student in Chile. Because telephone calls were prohibitively expensive, my dad suggested she call her family at home by visiting a ham friend of her host family who would then make contact with an American ham who could then phone my parents - awkward, but better than nothing for a homesick teenager.

Suddenly, much of the energy and brainpower Ovide had thrown into his scientific research was diverted not only to the study of radio equipment and antenna design, but to electromagnetic theory, astrophysics, meteorology, and other such esoterica. Fortunately, his XYL (ex Young Lady - cringe - that is, his wife), having grown up surrounded by receivers and transmitters and steeped in the lore of Project Diana, wasn't fazed by the prospect of investing in an office full of radio equipment or planting a hex beam next to the house.

It turned out to be the perfect hobby, combining his fascination with electromagnetism and radio propagation with his extrovert's love of interesting and wide-ranging conversation (and no, it isn't all about radio equipment or whose tower is taller!). He has now talked with hams in 165 countries and counting, including a commercial airline pilot flying 40,000 feet over the North Pole enroute to China and a lonely sailor in the middle of the Pacific Ocean on a solo trip around the world. Some of his contacts are brief, but others are extensive and repeated, occasionally blossoming into genuine friendship.

Meanwhile, finding myself immersed once again in all things ham, I did a little research and discovered that no one had claimed my father's callsign since 1992, the year he became a "Silent Key" (SK). So I signed up for HamTestOnline, a self-paced programmed-learning course, spent a couple of weeks intensively cramming, and presented myself to the Witch's Hat Depot in South Lyon, Michigan to qualify for the technician (entry-level) license. The exam itself consisted of 35 multiple choice items drawn from a pool of 400 questions, so there were no surprises; the only thing that varied was the order in which the answer choices were presented, to prevent a test-taker from memorizing only the letters associated with each question.

As of March, 2011, the proud old call sign W2AXO is now back in Stodola hands, waiting for a member of the next generation to take up the mantle. But don't expect to find me by calling CQ; I'm happy to leave broadcasting to my more gregarious husband.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed