* * * * * * * * * *

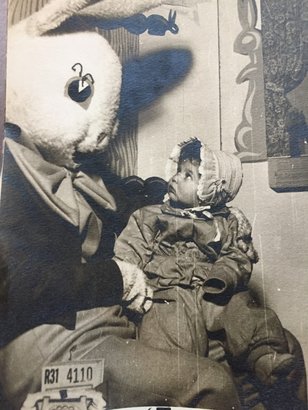

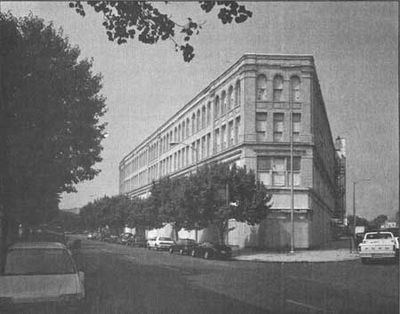

Bunnyland, as I recall, was located in Steinbach’s, which at that time billed itself as “the world’s largest resort department store.” The Asbury Park Steinbach’s, founded in the late 19th century, was the flagship store of what eventually became a chain, with branches dotting the Jersey shore. The store later fell on hard times after racial tensions flared in Asbury Park and was permanently shuttered in 1979, but when I lived there Steinbach’s was in its heyday. The trapezoidal “flatiron” style building that I recall, on Cookman Ave - a real eye-grabber - had been built in the 1930’s with four floors and a basement; by the time I arrived on the scene, a fifth floor and a clock tower had been added.

* * * * * * * * * *

Even for those of us who weren't particularly religious, Easter was a wonderful, happy holiday that signaled the arrival of Spring - a time of rebirth, a time when we could don our fanciest finery without freezing our bare legs, a time when we could start dreaming about summer vacation, about hunting for lady slippers and catching box turtles.

It also brought out our latent artistic impulses. When it came to the dyeing and decorating of eggs, families aligned themselves in two camps, those who hard-boiled their eggs and a smaller faction that hollowed them out. We were in the latter camp (and for that reason I still have eggs decorated by my daughters when they were children). We punctured both ends of the eggs and then blew on one end, somehow avoiding the twin hazards of salmonella from placing our lips on the raw eggs and apoplexy from the eye-popping effort required to blow the entire contents of an egg through that minuscule opening. (Trust me, this is no easy task, especially if you want the holes to remain small and inconspicuous. I usually ended up cheating and making the pinholes a little larger. It also helps to break up the yolk with your pin.)

The night before Easter, my mother filled our baskets (each of us had her own, recycled and restocked year after year) with Easter grass, the eggs we’d decorated, and a mouthwatering assortment of chocolate bunnies, jelly beans, and gumdrops. (No peeps - those weren’t mass produced till 1953.) My own favorites were those large crystallized sugar eggs with windows looking into a miniature alternative universe - not because of the sugar (though that was delicious when the confection finally dried out and crumbled) but because I liked to fantasize about crossing through that window into my own little Wonderland. You can still buy these eggs but somehow the interior landscape doesn't seem nearly as elaborate or compelling. Or maybe it's I who have changed.

After the baskets were assembled, my mother hid them, and the next morning we had to search for them. And by "hid them" I mean she really hid them, and never in easy, obvious places. One year she hid Sherry's basket in a seldom-used closet and swarms of ants found their way to the candy, so Leslie and I had to share our goodies with our little sister. Life’s like that sometimes.

Later in the day, having already stuffed ourselves with candy, we gorged on ham with pineapple slices studded with cloves, or perhaps on roast lamb with green mint jelly - both typical Easter fare of the era. Only Thanksgiving was a more tradition-laden dinner. For our friends who gave up something they cherished for Lent, the Easter feast ended forty days of deprivation. We enjoyed the goodies without the deprivation. Life’s like that sometimes, too.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed