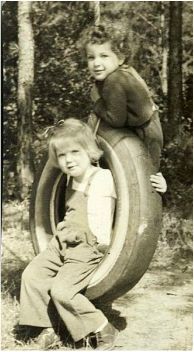

Sally and I in the tire swing.

Sally and I in the tire swing. **********

Sally was my very first real friend. In fact, in a way I knew her before I was even born, since our parents were already friends with each other. I can’t remember a time when I didn’t know Sally.

When you’re very young, everyone seems to be one-of-a-kind and larger than life, and my memories of Sally are almost psychedelically vivid. They are largely confined, however, to our first twelve years, before my family moved away from Neptune. We were truly just kids, and when I told [Sally’s sister] Helen I’d write a brief memoir I forgot about how solipsistic kids are. Most of my childhood recollections of Sally are actually at least as much about me as they are about Sally. There was the time I told Sally the “facts of life,” after having “the talk” with my mother, for example, and the time I gave Sally the lowdown on Santa Claus - both of which landed me and my big mouth in deep hot water with Sally’s mom Mary Jane! Harder to remember are the kind of anecdotes that would reveal Sally’s character or shed light on the really nice kid she always was and the adult she eventually became. That said, I’ll do my best with this task and hope Sally will shine through.

When I was very young my family lived in a rented home (or part of one) down near the river and I can’t remember exactly where the Evers lived, though I think it was far enough that you had to drive to get there. But when I was around five we moved to the corner of Pinewood Drive and Hampton Court, and not too long after that the Evers’s moved to Riverside Drive near its intersection with Pinewood Drive, just a couple of blocks away. From that time on, the children from the two families were inseparable. Mary Jane became my “other mother,” and Sally and Helen both told me how warmly they remember my mom. (I was always a tiny bit afraid of Jim, Sally’s dad!) The black cat with whom my own children grew up was named after the Evers’s black cat – Rasputin. It’s a great cat name and I learned a little Russian history in the process.

Life as a child in Shark River Hills in the 1940s was in many ways quite idyllic. We went out to play in the morning and often didn’t show up again till it was time to eat. (If moms did that today they’d probably have Social Services on their doorsteps, but somehow we managed to thrive.) Here are some of the things Sally and I did together: bike rides down the hill (how steep it seemed then! and we did it “no hands”) and on to the Cracker Barrel to buy a candy bar or an ice cream cone; scary safaris in the deep, overgrown ravine next to the Evers’ house; hikes in the woods in search of acorns (plentiful) and lady slippers (rare); catching box turtles and painting our initials on their backs in hopes they’d return the following year; long lazy summer days on our front porch playing jacks, pickup sticks, Parcheesi, and canasta. And of course no account of Shark River Hills in the 1940s and 1950s would be complete without a mention of the Clubhouse, a community center near the river where everyone young and old gathered for activities ranging from knot tying classes to potlucks to beauty contests. I recently sent Sally a jpeg file of myself in a “Tom Thumb Wedding” at the Clubhouse, in which Eddie Jackson and I played Jim and Mary Jane Evers. (Sally ruefully complained that her memory was horrible – she couldn’t remember Eddie Jackson at all.)

Good-sized families were the rule rather than the exception in those days. At first there were only Sally and me and the “Little Kids,” Barbara and my sister Leslie, whom we played with, fought with, hid from, and (I fear) teased mercilessly. (Sorry, guys!) The Evers clan eventually expanded to include Sally Jane, Nancy Jane who died in infancy, Barbara Jane who played with my sister Leslie, Billy (who understandably believed his name to be Billy Jane), and Helen Jane who played with my sister Sherry; five years after Sherry my brother Bob arrived, and sometime around then came Susan Jane, with whose birth Sally finally outstripped me in the sibling department – 4 Stodolas and 5 surviving Evers’s in all. We moved too soon for Bob and Susan to be fully incorporated into our little social system, though I well remember what a cutie little Susie was. In fact, all the Evers kids were attractive children. Sally was an adorable little girl, with straight strawberry blond hair, maybe a little tomboyish - a real kid’s kid. I should add that she was always quite a bit taller and heavier than I was, and I sometimes ended up with her hand-me-downs. When I left Neptune I was still a lot smaller than she was – so what a surprise to return for a visit and discover that I towered over her by 3 or 4 inches. She had stopped growing but I had not – my first lesson in the diverse patterns of child development!

Later in childhood we both branched out and developed other friendships. I became very close to Joyce Traphagen and Sally began a deep and lasting relationship with Anita Danko, to name a couple. But for as long as the Stodolas remained in Neptune, the strong bonds persisting from the time when we were almost sisters and essentially shared two mothers never entirely disappeared. Although then, as now, interactions among groups of girls could become complicated and even stormy, I can’t remember ever seriously quarreling with Sally. We must have had our share of tiffs, but unless someone or something else competed for our attention, we just sort of naturally gravitated to each other, as you can see in the Brownie troop photo I sent [BELOW].

Later on, thankfully, all that changed. In 1996, after I wrote to Mary Jane soliciting a contribution to a collective memoir of my mother, Sally volunteered her own reminiscences. “I remember your home very well,” she wrote, “and I think that…is because Elsa [my mother] made it a welcoming place. When I’m ‘home,’ I walk my dog around Pinewood [Drive] and I always look at the Stodola’s house and am glad it’s there.” After that Sally and I remained in fairly regular communication. She was very thoughtful about relaying messages to and from Mary Jane and later about updating me on Mary Jane’s condition. Her e-mails, though short, were always so sweet and gracious and self-effacing that they left me with a warm glow for the rest of the day. After Mary Jane died, she wrote to say: “Mother passed away on Sunday. It was peaceful and I’m very grateful for that. Just wanted to let you know since she was a part of your life, too, and she really enjoyed hearing from you.” She added that my mother had meant a lot to Mary Jane, who continued to the end of her life to tell “Elsa stories.”

One last interaction that I’ll always think of as pure Sally: In early 2010 she wrote to congratulate me on the publication of my self-help book for women smokers and added, “Being one of the absolute idiots who is still smoking, I shall go look it up.” When I offered to send her a copy, she replied, “Please, please, please DON’T send me your book! I’ll get it myself and you can autograph it for me at the reunion! I MUST support literary endeavors!!” She later reported that she had indeed bought the book from Barnes & Noble and was looking forward to reading it. That was one of my last e-mails from her.

The reunion she was referring to was of course the Neptune High School Class of 1960’s 50th, scheduled for late September, 2010. Sally warmly welcomed my plans to attend as an “honorary member” and reconnect with old friends from Summerfield, and we both looked forward to seeing each other again. So I was shocked beyond words when I arrived at the event, asked about Sally, and was told she had just died. My immediate reaction was that they must be talking about Mary Jane. I kept asking, “Are you sure? Are you really sure?” But no, sadly, it was in fact Sally, taken from us far too early, only a few months after her mother passed away. That’s not the way things are supposed to happen, and how I wish it had been otherwise. Rest in peace, Sally. You will always be an important part of my childhood iconography; but I’m also glad we got back in touch in later life and grateful for the opportunity to find out what a kind and generous person you turned out to be – not that I’m a bit surprised!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed