In late 1940, against the backdrop of a long-simmering war that was starting to boil over, President Franklin D Roosevelt was preparing for his upcoming State of the Union address, struggling to find a way to express his longstanding conviction that the our response to any world crisis, whatever it might be, should not be simply an expression of fear. (“The only thing we have to fear is fear itself,” he had famously said in 1932, speaking not of war but of the Great Depression.)

Then, on January 1, 1941, while crafting his third draft of his message to Congress, Roosevelt was struck by what he believed to be an inspired way of encapsulating his vision for both America and the world - that is, by enumerating what he called “The Four Freedoms”: freedom of speech, freedom of worship, freedom from want, and freedom from fear. The peroration he dictated to his secretary at that moment was retained almost verbatim in the actual speech five days later.

How disappointed Roosevelt must have been, then, when the major American newspapers, while covering the address in detail, pretty much ignored the four freedoms passage. Even after the US entered the War in December of 1941, polling results showed that although 80% of Americans responded favorably to the underlying ideals, fewer than 25% could name even one of Roosevelt’s “Four Freedoms”, and 61% had never even heard of the four freedoms at all. As a catchy slogan Americans could unite behind, the four freedoms were a nonstarter.

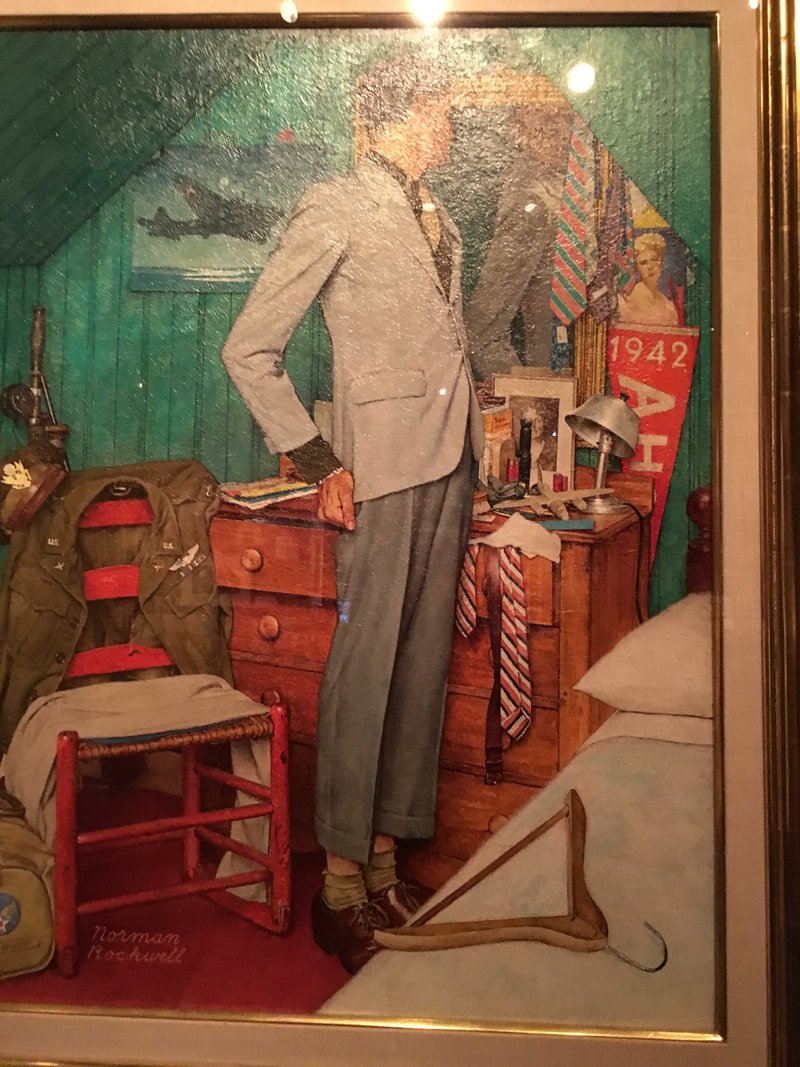

"The Four Freedoms" on display at Camp Atterbury.

"The Four Freedoms" on display at Camp Atterbury. Images and descriptions of these beloved paintings can be seen here. They appeared as covers on four consecutive weeks of the Saturday Evening Post in February and March of 1943, as well as on posters issued by the US Government Printing Office and on postage stamps. A photograph in the Camp Atterbury, Indiana Archives dated April 12. 1943, showing a WAC and a soldier flanking a four-freedoms poster, suggests that they were widely distributed on military bases (likely including Camp Evans).

As I wandered through the aisles, I felt sure there was a blog post here. After all, Rockwell’s fame as an artist/illustrator peaked between 1941-1946. My parents subscribed to the Saturday Evening Post, for which Rockwell created more than 300 cover illustrations over the course of his 47 year association with the publication. I remember looking forward to each issue as soon as I was old enough to read, always hoping Norman Rockwell’s instantly recognizable work would be featured on the cover, since I enjoyed both the visual humor and the satisfying sensation of “getting it.” And yet I can’t recall any specific discussions of Norman Rockwell, and when I polled my siblings, neither could they. I can only conclude that Norman Rockwell was so much part of the water we swam in, the air we breathed, that his work was too familiar and omnipresent to be worthy of comment.

One outcome of all this introspection was Rockwell’s focus on a series of “characters” who came to stand for the American “can do” response to wartime mobilization. Perhaps the most notable was Private Willie Gillis, who appeared on several Post covers. Another, painted not long after the Four Freedoms tetralogy, was Rosie the Riveter, who appeared on the cover of the Saturday Evening Post on May 29, 1943.

I always loved the idea of Rosie because of what she represented - a woman who, when the men were called away to fight a war, willingly did the work of the world, supplying both wartime needs and what was needed on the home front, and was paid for it. But no matter how often she was admonished that once the War was over she would have to cede her job to a returning serviceman who needed the work to support his family, that genie could never quite be put back in the bottle, and Rosie unexpectedly turned into an agent of radical social change.

Rose Balaban LaMay Stodola (1921-2017)

Rose Balaban LaMay Stodola (1921-2017) So imagine my surprise, as a self-professed Rosie buff, to learn at the Rockwell exhibit that 1) Norman Rockwell had painted an enormously popular picture of Rosie the Riveter, with which I was completely unfamiliar; and 2) the image I and most others knew as Rosie was not the one Rockwell had painted and was possibly not even Rosie.

How could this be?

Norman Rockwell's Rosie the Riveter (1943)

Norman Rockwell's Rosie the Riveter (1943) The song inspired a number of paintings, of which Rockwell’s was the most popular and widely known at the time, but far from the only one. Rockwell’s Rosie wore a blue jumpsuit, with a rivet gun in her lap, a sandwich in her hand, and a copy of Mein Kampf beneath her foot. Her lunchbox was labeled “Rosie,” a backlink to the popular song by Evans and Loeb. Rockwell’s Rosie had red hair and was so hefty and muscular that Rockwell felt he had to apologize to his neighbor Mary Doyle, a much more petite woman who had served as his model.

The painting behind me in the upper right is the one now celebrated as Rosie.

The painting behind me in the upper right is the one now celebrated as Rosie. And there things stood for decades, until circumstances conspired to create a need for a heroine like Rosie. The 1980s marked the start of 40th anniversary celebrations of World War II (including my father’s largely unsuccessful attempt to commemorate Project Diana in 1986). It was also the time in which the second wave of feminism was winding down, having for the most part (with the glaring exception of its failure to pass the Equal Rights Amendment) met its goals, and many women were encouraged by the legislative and social victories their efforts had brought about. The National Archives, faced with the budget cuts of the Reagan era and looking for a way to generate income by capitalizing on both World War II nostalgia and the feminist wave, somehow hit upon the Miller image, licensed it, and plastered it on tee-shirts, mugs, and other souvenirs. And the crowd went wild!

Although licensing Rockwell’s Rosie would have been a much more expensive proposition, there are probably additional reasons why his painting was passed over for this campaign. Miller’s portrait, more feminine than Rockwell’s, was less likely to create uneasiness around the issue of gender bending. The Miller painting is also less of a period piece; “We Can Do It,” though at the time it implied “win the war,” translates more fluidly to the hope of achieving other goals than does the symbolism of Rosie tromping on Mein Kampf. The choice of Miller’s painting, far from being obvious, was a stroke of genius. Its moment had arrived.

What is harder to fathom is the alchemy by which Miller’s painting came to occupy Rosie’s identity, probably displacing Rockwell’s Rosie for all time.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed