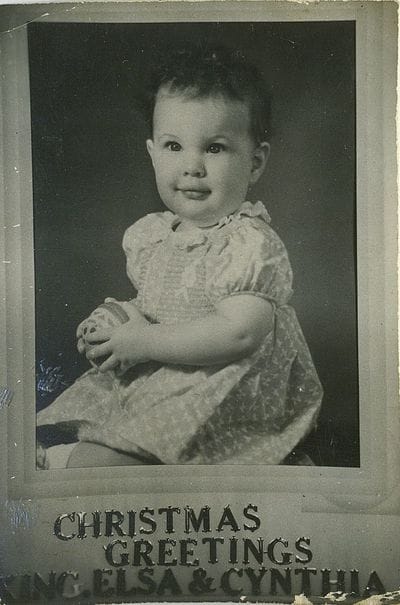

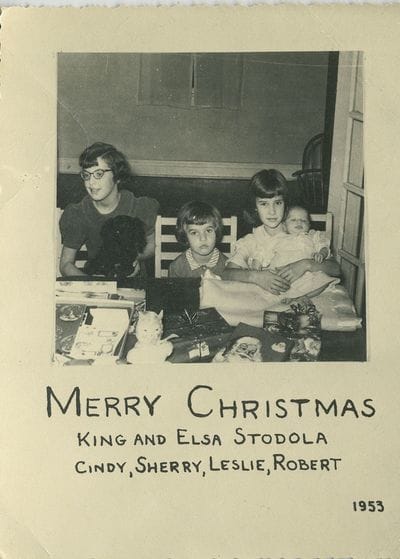

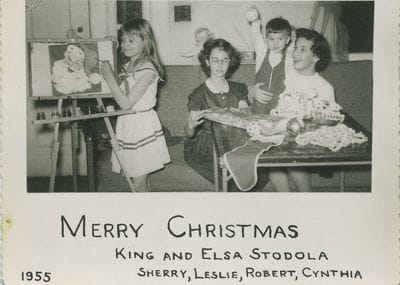

My response started out, “Christmas was the biggie.” The rest of this post is adapted from the essay I wrote for him then.

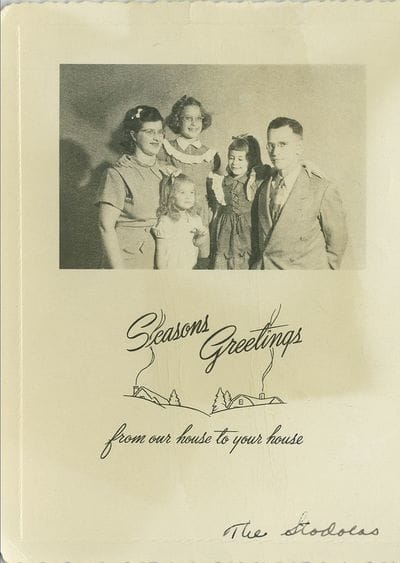

Our Christmas actually started with Thanksgiving - and anyone who denies that it began so early back in the "old days" or blames Hallmark for rushing the season is mistaken. We usually went to my father’s parents' home in Oakland NJ, a couple of hours' drive from Neptune, along with my uncles Quentin and Sid (my father's brothers), their wives, and Quentin’s three children, who were about our age. Of course we had turkey, stuffing, and all the fixings. My mother made apple and mincemeat pies and to let the steam out, she took a sharp knife and made dotted lines in the crusts that read TA ['tis apple] and TM ['tis mince].

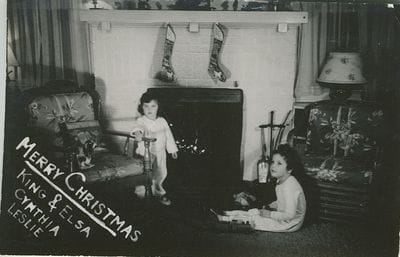

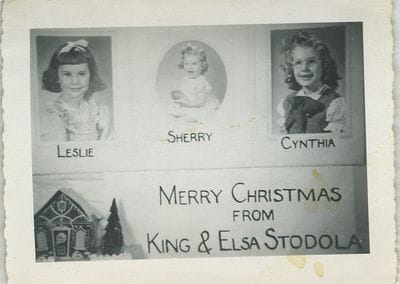

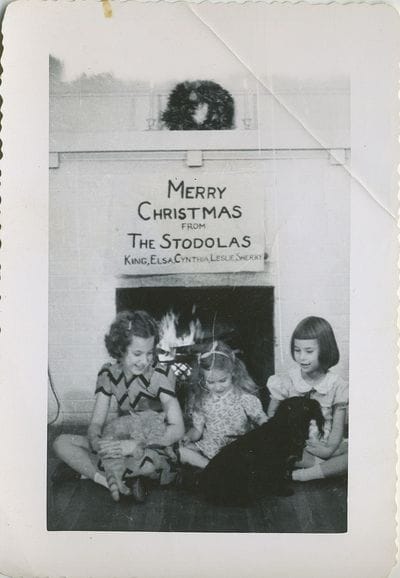

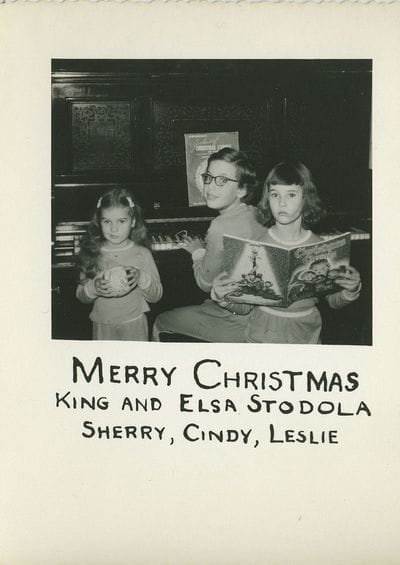

A couple of weeks before The Day, we decorated the house. My mother had a creche that we set up on the mantle, and even though we weren't particularly religious, I loved the baby Jesus and the whole family tableau. (I still do.) Right below them hung the stockings awaiting Santa's attention - an interesting juxtaposition of Christian and pagan symbolism, though not one we thought much about at the time. We also had a little cardboard village with colored cellophane windows and holes for Christmas lights, which she arranged on the piano. A wreath went up on the door.

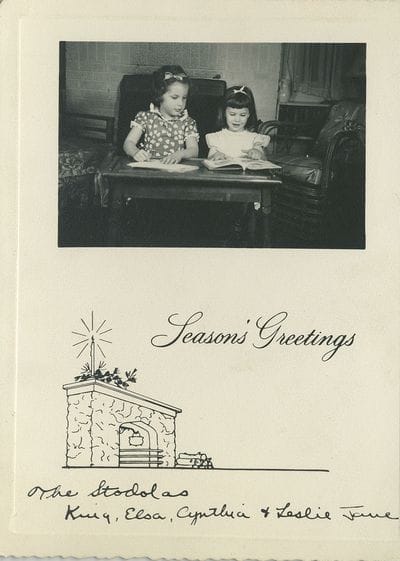

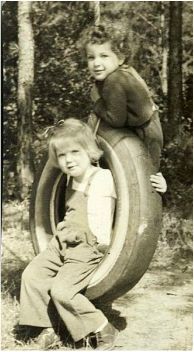

My father set up the tree in a semi-finished "game room" in the basement, near the pingpong table. The beloved box of ornaments came down from the attic, and we competed to be allowed to hang our favorites. Another predictable squabble was sparked by the silver foil icicles: I liked to hang them slowly and painstakingly so they would look like real icicles, while my sister preferred taking clumps of the stuff and flinging them at the tree. These mini-crises resolved, we artfully arranged our gifts under the tree - all but the ones from Santa, who didn't visit till Christmas Eve after all of us (including, we supposed, our parents) were sound asleep. (I'll never forget how proud I was when I was deemed old enough to be dropped off at Woolworth’s in Asbury Park to shop on my own, using the money I saved from my allowance by depositing fifty cents per week in a "Christmas Club.")

My parents always hosted an Open House for all the neighbors (children and adults alike) on Christmas Eve. During the preceding week, we made dozens and dozens of cookies - including sugar cookies, which we decorated with red and green sugar, and Tollhouse cookies, made by following the recipe on the back of the Nestle’s package, which magically and consistently produced the Best. Ever. Chocolate. Chip. Cookies. Out came the two fruitcakes, dark and light, for one last splash of brandy. Just before the party my mother prepared two batches of eggnog, nonalcoholic for the kids and most definitely alcoholic for the adults. We donned our Christmas finery and were allowed to stay up late. Years later, one of the neighborhood girls told me she was so inspired by these parties that as an adult she has always given a Christmas Eve Open House of her own.

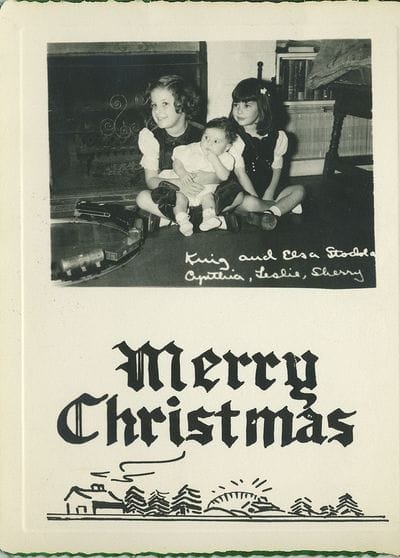

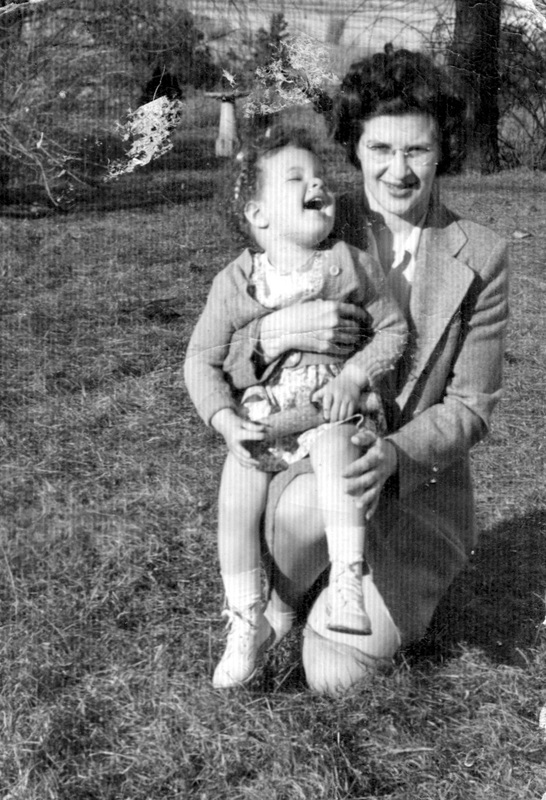

After all the guests had gone home, we put on our foot pajamas and snuggled up to listen to "The night before Christmas"; then it was off to bed with us so we wouldn't be too tired the next morning. Not a problem for me; I was almost always the first one up. But we still had to wait for our parents to get up before we were allowed to go down to the basement and start opening our gifts - which seemed like forever but was probably more like half an hour. We had made our Christmas lists and I usually got exactly what I'd requested, plus lots of other stuff. One year I asked for a Nancy Lee doll but stipulated that I wanted her wrapped so I could be surprised when I opened the package. This turned out to be a bad call because she didn’t come in a box, and her gorgeous red hair ended up with a bad case of "wrapping paper head" that never quite went away no matter what I did.

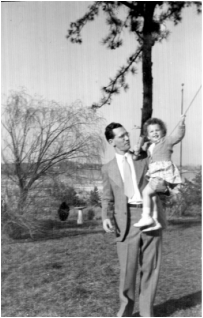

When I was around five, my father bought us an electric train. After we went to bed on Christmas Eve, he stayed up long into the night laying the track so that the train would disappear down a hallway and a couple of minutes later reappear through the dining room. That year he, not I, was the first one out of bed on Christmas day. The train was a big hit with all of us but no one was more excited than my dad. If you want to make an engineer happy, just give him a model train and a whole day with nothing else to do but play with it.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed