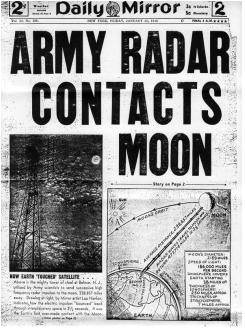

News of the experiment made banner headlines and flashed on movie screens across the country and around the world. The local newspaper, understandably reveling in its scoop, described it as "one of the most brilliant scientific accomplishments of all time." Anyone old enough to have lived through the Apollo 11 era, and to remember how that "one small step for man" captured the public imagination, probably has a fair idea of the impact made by Project Diana.

Project Diana and its culmination on that chilly winter morning came at an almost magical moment in time. For Jack DeWitt, leader of the project, it represented a once-in-a-lifetime window of opportunity. His team, at the height of its powers and uniquely configured to carry out a wartime mission that was no longer needed, was about to be disbanded. DeWitt's script called for him to retreat quietly into civilian life. Instead, in his few remaining months at Camp Evans, he chose to attempt one last tour de force and fulfill his longtime dream of shooting the moon. It also occurred at a singular nexus in American history - looking back on our emergence from isolationism and the deprivations and horrors of World War II, and ahead to the baby boom, suburbanization, the Cold War, radical changes in the lives of both men and women, communications breakthroughs, and an astounding acceleration in the pace in scientific development.

I originally conceived Project Diana: The Men Who Shot the Moon as a tribute to Col DeWitt, the other four members of his team, and their Camp Evans colleagues on whose additional contributions the team depended. But always, in the back of my mind, lurked the niggling sense that there was more to be said, and that Project Diana might constitute an interesting lens for examining some of the transformations and dislocations occurring in the US in the aftermath of World War II. Today, on the 70th anniversary of the first moon bounce, I am launching this blog to extend the website's mission through explorations of Project Diana's historical, sociological, political, and scientific context, as seen from the perspective of the tiny coastal New Jersey community where fate in the form of Camp Evans deposited my parents and their neighbors.

I believe I'm reasonably well-poised to chronicle the life and times of Project Diana. Although I'm not a professional historian or sociologist, I grew up in Diana's shadow on the Jersey shore. My father, E. King Stodola, was the project's chief scientist, and I have numerous documents, photographs, and clippings pertaining to his work. My earliest playmates were other Project Diana and Camp Evans "legacies." And although I'm not an expert in RADAR or EME, I boned up enough to earn my amateur radio technician's license and reclaim my father's call sign, W2AXO. (My husband, Ovide, an active ham who shares my affection for Project Diana, has agreed to try to keep me out of trouble on the more technical aspects of the feat.) I hope my readers will add value to this endeavor by submitting comments, corrections, and contributions.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed