Although the US had kept a wary eye on developments in Europe (Asia not so much), until now it had maintained a staunch neutrality, its populace deeply divided on whether America should be involved in the war effort in any way. All that changed with Pearl Harbor. Within hours America was on a wartime footing. Soon films about military life and lovers separated by war would crowd out Citizen Caine and Dumbo in the movie theaters. Soon “Boogie Woogie Bugle Boy” and “I’ll be Home for Christmas” would dominate the airwaves, along with revivals of World War I hits like “Over There.” Soon deprivation and shortages of building materials and consumer goods would become the norm. Soon admonitions like “Remember Pearl Harbor!” and “Loose lips sink ships” would become part of our daily conversation.

Much has been made of the parallels between Pearl Harbor and 9/11. Both were unexpected attacks on iconic homeland targets, both inflicted a shocking amount of damage, both resulted in thousands of casualties, and both brought a sudden reveille to those who thought the world outside our borders could simply be ignored. Both drew the US into many years of armed combat. Whether the long-term ramifications of 9/11 can possibly match the political, economic, sociological, and cultural dislocations that followed World War II - the decades-long dominance of the US on the world stage, the Cold War, the increasing pressure for gender and racial equality - remains to be seen. But the analogy is useful in giving those too young to remember Pearl Harbor at least a hint of its transformative effect on life in America.

* * * * * * * * * *

For both the men and women of the Camp Evans community, the impact of Pearl Harbor was, if anything, magnified by the circumstances in which they found themselves - that is, in a new, ad hoc community, with nothing in the way of roots or shared traditions; and with all the men suddenly on high alert, aware that if the Axis powers knew what was going on at Camp Evans it too could become a prime target.

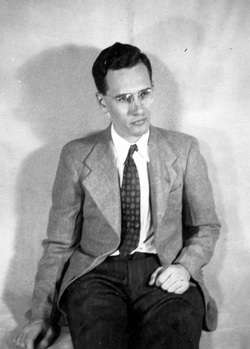

Much of what I know about this era of my father’s life was gleaned from an oral history interview I conducted with him in 1979. He told me his initial assignment was at Fort Hancock, “an isolated peninsula up near New York City; but we were eventually transferred to the old Marconi Radio Building down at Belmar [which the Army had only recently acquired].” To minimize his commute and allow him to ride his bike to work sometimes (they only had one car), my parents moved at around the same time from Long Branch, their first NJ home, to Shark River Hills.

If my dad was looking for excitement, he almost certainly found more than he’d bargained for. My parents and their friends were of course keenly aware of the war in Europe - how could they not be, given my father’s line of work? - but it was someone else’s war, not theirs. Preoccupied with unpacking their boxes, adapting to their new life, thinking about having children (a question of when, not if), they were as oblivious as most other Americans were to the fact that war was about to lap up to our own shores, and even more surprisingly, at the hands not of Hitler but of the Japanese: “Pearl Harbor...was a tremendous shock to us. I guess if we really stopped to think of it, we would have realized that something like this was inevitable, because Hitler's intentions were very clear - dominate the world! - and he would form whatever alliances and whatever he needed to do it. But when the shoe dropped, as it were, it was a great shock. It was a Sunday morning, and we were madly telephoning - how can we get out and man those radar sets and do something about it? - a panic, pretty much of a panic.”

My father added, “[It turned out] there was no attack on the East Coast, at least not at that time - although there was some later.” I didn’t pursue this almost offhand observation at the time and neither did he. It now appears that U-boat attacks on shipping along the East Coast were more extensive than was ever officially revealed, and I can’t help wondering if my father knew more than he was letting on.

Several workplace changes resulted almost immediately from the attack on Pearl Harbor. Security, already tight, was strengthened even further. My father's work took on a laser-like focus on the military applications of radar: “I eventually wound up heading what was called the Special Developments section with about 15 or 20 people in it and we did some very interesting work in radar [including the Army’s first moving target search radar].... I think some of it was very original.” Another dramatic change was in their work schedules: “Overtime became the rule rather than the exception - in fact, we worked pretty much a six-day week.”

* * * * * * * * * *

When the Camp Evans wives were parachuted into the unfamiliar Jersey Shore culture, they found themselves quite isolated, their social circle largely defined by their husbands’ work ties. After the sky fell on December 7, 1941 and their husbands started spending more and more time at work, they clung to each other all the more tightly for solace and companionship.

My mother’s closest friend from that era was Mary Jane Evers, an outgoing woman with a wry sense of humor. (Decades later I named my black cat after her black cat, “Rasputin.”) Mary Jane had a way with words and for many years wrote an amusing column in the Asbury Park Press called “We Took to the Hills” that went well beyond the demands of the genre (which tended to focus on who had tea with whom or presided at the ladies’ auxiliary meeting). In 1996, when I asked her to contribute to a “collective memoir” on my mother, she responded with a charming, breezy essay, scrawled in longhand, portraying both the impact of Pearl Harbor and her evolving friendship with my mother.

Although she was still living in West Long Branch at the time of Pearl Harbor, she was obviously already very tuned into life in “the Hills” and the Evans Lab community: “You must remember we were all ‘strangers in a strange land,’ so to speak. Our husbands had been assembled from all over to nurse the infant Radar labs and then the electronics labs. None of us had family nearby; shortly after we met, the attack on Pearl Harbor [occurred]; we each had 4 gallons of gas a week for the family car, and meat and sugar rationing. We lived in a summer development, in homes not equipped for year-round living, and about 3 macadamed roads which the Army had done to get to their own properties in the Hills and to allow the personnel to get to work.”

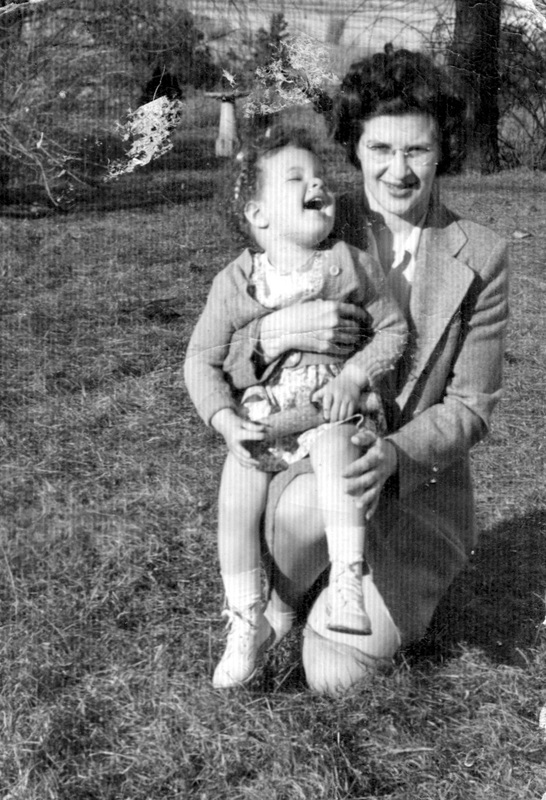

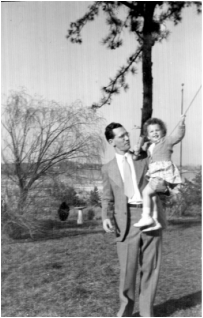

My mom and Mary Jane didn’t formally meet until sometime in 1944, when each of them had a toddler daughter and Mary Jane was pregnant with her second child. By late fall, Mary Jane was going through a very rough patch. Her new baby had recently died at the age of three months, and her husband Jim, who like my father had joined the Radar Division at Evans shortly before Pearl Harbor in 1941, was away on “travel duty.” Impulsively, my mother phoned and invited her to join them for Thanksgiving dinner. Their friendship was cemented with that gesture.

Aside from their children, the other perennial conversation topic was money, or more accurately, the lack of it. According to Mary Jane, the pay was not generous even by wartime standards: “Civil Service personnel were not among those getting raises in Congress. The general public, from what I have learned, figured they had had money all thru the Depression when everyone else was broke, so they could just wait.”

“Budget problems were ever on our minds," she went on to say. "Your [parents] would have some ‘interesting’ discussions when the bills came in. My daughter Barbara vividly remembers hearing Elsa say, “There’s always too much month at the end of the money!” The women raided their kids’ piggy banks (we all had piggy banks, which were supposed to teach us to save our money), and as my mother commented to Mary Jane, “By the time I pay the children back, I’m broke again!” Elsa and Mary Jane bartered babysitting time by deliberately joining organizations with different meeting schedules: “She was in the AAUW and I was in the League of Women Voters; she was a member of the local Fire Auxiliary and I was a member of the Hospital Auxiliary.“

At the end of this litany, Mary Jane worried she might have left me with the impression that the lives of the Evans wives were all about “money-grubbing.” Of course, none of us was suffering from malnutrition or doing without the basics of food, clothing, and shelter. The point was that money was needed not only to provide the necessities of life but, in a world filled with bad news and uncertainty, to allow for the comfort of a few extras - “a spot left over for simple parties, cheap beer and soda and birthday cakes.” Making things come out right, making ends meet, making it possible to have birthday cakes as well as Spam - that was a job that fell to the women. It was part of their contribution to the war effort, and they took it seriously.

* * * * * * * * * *

How did the children of the Camp Evans community fare during Pearl Harbor and its aftermath? I was born just over a year after Pearl Harbor and have only fleeting memories - if indeed they are authentic memories at all - of the War years. Many of the facts of wartime life were part of the air we breathed. Yes, we ate Spam for dinner. Yes, we observed blackouts and dim-outs to avoid bringing unwanted attention from the German U-boats to American supply ships. Yes, we shared in the American love affair with the radio and tracked the terrifying narratives it brought into our homes. Yes, a chronic state of low-level deprivation was a part of our daily existence.

But in some important respects we were sheltered. The men - whether they were in the military or, like my father, civilians employed by the military - were doing work deemed critical to the War effort and therefore spent the War years on the homefront. They may have left for work early in the morning and arrived home late at night, but at least they were there, not thousands of miles away like my father-in-law, who spent four years on the Italian front as an Army surgeon. Our uncles and cousins may have been in uniform overseas, but not our fathers.

So in a way we Camp Evans kids got the jump on the Fifties. At a time when other families were struggling to adjust and create a new normal, we were already there. The Baby Boom was already in progress. Sally, the oldest Evers child, was born on September 11, 1942 - 39 weeks to the day after Pearl Harbor. My mother suffered a miscarriage before I was born; otherwise my parents too would have had a “Pearl Harbor baby.” Perhaps that’s why, whatever arbitrary cutpoints the demographers adopt, I’ve always known in my heart of hearts that I’m a “Boomer.”

Our mothers also didn’t have to be hounded out of their jobs and back to domesticity, they’d been there all along. I’m not sure to what extent, if any, the resurgence of feminism rooted in the wartime increase of women in the workplace ever touched my mother. Much later she took a few education courses in the hopes of translating her college English major into a marketable skill, but by that time her health was starting to fail and her retooling scheme never got off the ground. Her ambition for her three daughters was that we should marry well, so that we too could have the privilege of staying home to care for our children. We all remember her saying, only half-jokingly, “It’s just as easy to love a rich man as a poor man.” Fortunately for us, in light of subsequent economic shifts that made the one-income family a luxury, as well as our own ambitions, we got quite a different message from our father, who presented his women colleagues as role models and urged us to take all the math and science we could cram into our schedules.

* * * * * * * * * *

My parents and their friends were part of what Tom Brokaw called the “Greatest Generation” - men and women born between 1901 and 1924, who came of age during the Depression and World War II, who shared a common core of values including honor, service, love of country and family, and personal responsibility, and who more than rose to the occasion when duty called. For better and for worse (don't forget the internment camps for American citizens of Japanese descent, or the abuse my pacifist uncle suffered as a Conscientious Objector during World War II), they shaped America as we know it today.

As Brokaw observed, it was sometimes difficult to coax their stories from them because of their conviction that they weren’t doing anything special, just honoring their commitments and doing what they were supposed to do. In this context, I feel fortunate to have obtained, without really planning to do so, the two eyewitness accounts on which the above narrative largely rests. And a big shout out to Bill and Helen Evers for sharing their childhood family photos with me. For more about the Evers's and their friendship with the Stodolas, read my post dated February 27, 2016 and elsewhere in passing.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed