In the minds of most Americans then and now, World War II was “Over There.” The home front was regarded not as a war zone, but rather as a base of operations for providing supplies and support. America was where Rosie the Riveter kept wartime production going so that our boys could go overseas where they were so badly needed. America was where homemakers like my mom, along with her friends Mary Jane Evers and Ruth Mofenson and all the other Camp Evans wives, got by on a ration of 4 gallons of gas per week so the War effort in Europe could be fueled.

And yet just days after Pearl Harbor, Hitler ordered an attack on America. He had been anticipating the entry of the US into the War, which would likely infuse American industrial might into the Allied effort, and believed that preventing the US from supplying Britain with fuel and arms would be key to a Nazi victory. The Nazis had been fighting what Winston Churchill dubbed the “Battle of the Atlantic" since 1939, including the use of Unterseeboote (U-boats) to attack Allied merchant shipping in an effort to counteract the naval blockade of Germany. The German Kriegsmarine was thus well-poised to add the US to its list of targets. Operation Paukenschlag (Drumbeat), a barrage of submarine attacks on American shipping, was launched in January of 1942, and soon Nazi U-boats were swarming up and down the East Coast, preying on American warships, tankers, tenders, and supply ships.

After a few months the Americans knuckled down and adopted more stringent measures. Blackouts were ordered and enforced, and my husband remembers being scolded, as a young child in Maine, for peeking under a cover draped over a radio to hide the light while the family listened to the news. Peacetime shipping lanes were abandoned and shipping was restricted to daytime in convoys, escorted by British corvettes specially designed for anti-submarine warfare. Unpredictably-timed daily patrols were implemented, and gradually the German “wolfpacks” retired to happier hunting grounds elsewhere in the Atlantic. Eventually German codes directing sub maneuvers were broken by the Allies, and Operation Drumbeat officially ended in July of 1943 - although periodic submarine attacks on American ships continued until just a few days before Germany surrendered in 1945.

Still, although the Allies technically won the Battle of the Atlantic by virtue of winning the War, the overall picture for America did not exactly smell like victory. Indeed, one historian claims that Operation Drumbeat “constituted a greater strategic setback for the Allied war effort than did the defeat at Pearl Harbor." More ships and more lives were lost in the former than in the latter, giving lie to the popular notion that Pearl Harbor and Nine-Eleven were the only two successful strikes against the American homeland. Yet in all, only a handful of U-boats were destroyed.

* * * * * * * * *

So where was everybody while all this was happening?

A few people, of course, were of necessity informed about what was going on in their back yard. My father, in our oral history interview in 1975, told me with perhaps less than complete candor, “There was no attack on the East Coast, at least not at that time [of Pearl Harbor] - although there was some later.” (A better interviewer than I would have pressed him on this issue.) His brother Sid, who was in the Coast Guard stationed in Boston, surely knew. The “need to know” list, however, was apparently astonishingly small - reflecting the succinctly-stated policy of Ernest J. King, Chief of Naval Operations: “Don’t tell them anything. When it’s over, tell them who won.” (This is the same Admiral King whose daughter once remarked that her father was very even-tempered: "He's always in a rage.")

Nonetheless, many individuals were uncomfortably aware that something was afoot, especially after blackouts were systematically mandated and enforced. A number of ships were torpedoed by U-boats within sight of New York and Boston. Other residents near the shore reported seeing eerie lights and other unnatural phenomena that were difficult to explain. Further news about the German presence trickled out when a couple of unsuccessful attempts to land German spies on American shores via U-boat were foiled.

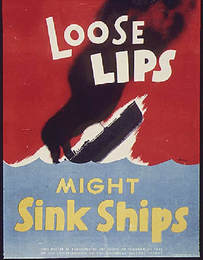

American World War II poster by Seymour R. Goff. (The original "might" quickly dropped out.)

American World War II poster by Seymour R. Goff. (The original "might" quickly dropped out.) Partial knowledge and half-truths, of course, bred speculation and rumor - something that can be more dangerous than the truth. On Saturday August 7, my grandmother noted in the journal she kept in the summer of 1943 during her annual stay on Cape Cod, “Gradually the news comes in with the story of the Busy Blimps. We hear a large convoy was going by and was attacked by a German submarine; that it has been sunk somewhere off our shore. We hear distant guns but never know whether they are real, or target practice somewhere." She drew pictures of her neighbor’s clothesline on successive days, hoping to discern patterns in the size and spacing of the hanging towels that might, just might, be coded messages. Less amusingly, she also identified a potential German spy among the customers at a local bakery. “The authorities think someone is acting as a German agent along our shore. I think so too, but probably have my eye on the wrong person.” Fortunately she was wise enough not to gossip about her suspicions; loose lips may sink ships, but false accusations can do their own kind of damage.

* * * * * * * * *

How close did Operation Drumbeat come to the Jersey Shore?

Very close indeed.

Here as elsewhere along the Eastern Seaboard, residents periodically reported seeing Allied convoys being attacked by the U-boats and being awakened at night by the sound of explosions at sea. But the most shocking evidence came to light in 1991, when a fisherman’s net caught on a massive object sixty miles off Point Pleasant, New Jersey. When a group of recreational divers made the 230-foot descent, they found an intact U-boat, along with its torpedoes and the remains of its crew. No records of attacks in the area or unaccounted-for U-boats could be found to identify the wreck.

Over the next six years, a team of professional divers led by John Chatterton and his partner Rich Kohler made it their mission to determine the identity of the wreck - dubbed “U-Who” because of the uncertainty. Their efforts were hampered by diving conditions so treacherous that they claimed the lives of three divers during the course of the exploration. (See Bernie Chowdhury's The Last Dive: A Father and Son's Fatal Descent into the Ocean's Depths (Harper Collins, 2000) for a heart-rending account of the deaths of Chris and Chrissy Rouse, an experienced father-and-son scuba diving duo.)

Chatterton and Kohler's first clue was the discovery of a knife inscribed “Horenburg,” the name of a Radio Operator assigned to U-869, a Type IXC/40 U-boat. Their initial elation, however, was dampened by the news that U-869 had been sent to Africa and sunk off Casablanca on February 28, 1945 by an American destroyer and a French sub chaser. Reluctantly, the “Horenburg knife” was discounted. In 1997, however, serial numbers and other conclusive evidence were recovered confirming the identity of the wreck as U-869. Evidently the commander, Hellmut Neuerburg, had never received the orders diverting the sub to Gibraltar and instead perished off the Jersey Shore just a few miles from where I lived in Shark River Hills; I was two years old at the time.

U-Who continues to hold its secrets close - though not for want of ink spilled on the topic. Chatterton and Kohler, as documented in Robert Kurson’s bestseller Shadow Divers: The True Adventure of Two Americans Who Risked Everything to Solve One of the Last Mysteries of World War II (Random House, 2005), concluded that the sub was probably sunk by one of its own acoustic torpedoes. Gary Gentile, another experienced wreck diver, hotly disputed this theory in his book Shadow Divers Exposed: The Real Saga of the U-869 (Bellerophon Bookworks, 2006), citing logs from two destroyer escorts suggesting that they had sunk the sub and also arguing that the damage was more consistent with the destroyer attacks. The United States Coast Guard’s official report, after a lengthy investigation, supported Gentile’s conclusion, but Chatterton and his colleagues continue to believe that the two destroyers attacked the sub after it had been struck by its own torpedo. The truth may never be known.

Yet another piece of the U-Who puzzle was added when a German named Herbert Guschewski, after watching a preliminary version of a 2004 PBS NOVA episode about the wreck entitled “Hitler’s Lost Sub,” approached the producers of the documentary. Guschewski had been the Second Radio Officer assigned to U-869 (and a close colleague of Martin Horenburg, whose knife had given the first hint about the sub's identity) but was hospitalized with pneumonia and pleurisy just before the boat departed and had thus been unable to accompany his crew-mates on their first and only voyage. An interview covering his recollections of life on a U-boat and his feelings about being the sub’s lone survivor is included in the final version of the NOVA program. It is worth watching.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed