On May 29, 1881, Joseph, a dry goods merchant, married Bertha Eilau. Joseph and Bertha had three children, Gilbert Isaiah (born in 1883), my grandfather Edwin Sidney (born in 1885), and Ruth, the baby (born in 1892). Gilbert listed himself as an editorial assistant on his World War I draft card but also stood as proof of a scientific bent in the family, having published an article in the January 1923 edition of the Scientific American about an ingenious device he’d invented for installation in taxicabs to allow the fleet owner to determine the time and distance covered in each trip. So my father’s engineering abilities and love of gadgets, though they probably surprised his artistic parents, apparently didn’t come from out of nowhere.

My grandfather must have displayed a gift for music early in life and was evidently encouraged to pursue it. By the time he was in his late teens or early twenties, he had achieved critical acclaim as a concert artist, including the obligatory Carnegie Hall recital, and was also working as a piano teacher. His advanced training included six years under the tutelage of Henry Holden Huss - largely forgotten now, but in his day a well-known American pianist and composer, and performances of his pieces can still be readily heard on youtube. They evince a conservative taste in music and are quite free of avant grade rhythms and dissonances. (It is worth remembering that Brahms lived until 1897, when my grandfather was age 12 and Henry was age 35, so the romantic tradition was hardly ancient history during that era.) The Henry Holden Huss collection is housed in the Music Division of the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts.

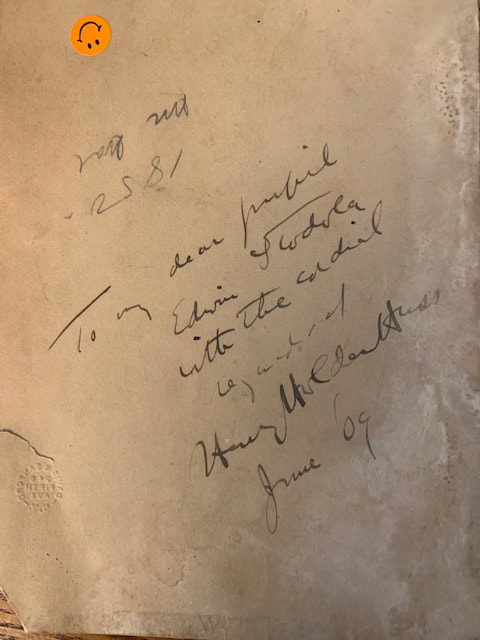

I’m not sure when these six years of study with Huss began and ended. My family “archives” includes a tattered photo of Henry Holden Huss and his wife, the American soprano Hildegard Hoffmann (clearly a marriage made in HHHeaven!), dedicated on the reverse “To my dear pupil Edwin Stodola” and dated June ’04. Or at least I think it says ’04. If so, it was likely a token or souvenir of Henry and Hildegard’s marriage, which took place in that same month and year, and the six years my grandfather studied with him must have included if not started with 1904.

(Florence) Beatrice King, born in 1889 in Savannah, Missouri, was the doted-upon only child of Arthur and Vergetta Sayers King. Like Edwin, she found her calling early in life and participated in theatrical performances as a child. Her training was in a profession that almost doesn't exist today, as an elocutionist or diseuse; perhaps the closest modern equivalent would be a performance artist. After finishing her secondary education she attended the Chicago Conservatory of Music and Dramatic Art, followed by postgraduate work at the Columbia College of Expression and the American School of Expression and Oratory. She then returned to Missouri and coached students in drama and public speaking. She also painted and wrote poetry and plays. She was sociable and effervescent and had a wide circle of friends. She must have dazzled the quiet Edwin.

Not long after, their Missouri saga came to an end, and by the time my father was born in October of 1914, they were living in Brooklyn. Now that my grandfather was back in New York, I wish I could report a reconciliation with his parents, but alas, that did not happen, then or ever. Edwin’s brother Gilbert, so far as I can tell, never married, and his sister Ruth, marrying late in life, never had children. So my father and (later) his two younger brothers were Joseph and Bertha's only grandchildren. My grandmother made a couple of valiant attempts to visit her in-laws, hoping the sight of their adorable little grandson would melt their hearts, but she was not invited in. Only now, through the miracle of ancestry.com, am I slowly piecing together my grandfather’s story and even tracking down a few cousins on the Stodola side.

This ushered in what might be called the Golden Age of my grandfather’s career, as a google search turns up several reviews of concerts and recitals in which he played pieces I could only dream of tackling. The oboist and musicologist Lisa Kozenko, in a doctoral dissertation focused on this era, describes “a musical reception in honor of the American baritone David Bispham (1857-1921) along with the Husses. The guests included the Vincent Astors, Carolyn Beebe, Elizabeth Sprague Coolidge, the Hermann Irions, Hugo Kortschak, Mrs. Ethelbert Nevin, and others. In its April 7, 1917 issue, Musical America reported that Huss was asked to improvise ('A thing which he does fascinatingly'). His student Edwin Stodola suggested “D B” as theme honoring Bispham: 'It was on that that Mr. Huss built his splendid improvisation, which won warm favor from all present.'”

So we have now arrived at the May 6, 1918 concert in Rumford Hall and my grandparents’ subsequent move to Boston, as described in my most recent blog post. Although I concluded in that essay that they had not moved to escape the pandemic, they almost certainly also did not move to advance Edwin’s career as a concert artist; if anything, probably the opposite. Although Boston was once the hub of the national chamber music scene, the center of gravity had by now shifted to New York City. Had he been bent on pursuing a concertizing career, my grandfather should have stayed put and remained under the wing of the Husses.

“Being a musician is not an easy profession in any era,” wrote Kozenko in her dissertation. "[By 1920], the competition from radio, recordings, jukeboxes and movies confronted anyone attempting to pursue a career in music.” The May 6 concert appears to have been almost a swan song. With a growing family and a pandemic emptying concert halls, he had likely decided it was time to shelve the dream of supporting his family as a musician and move on to a different life plan.

This is not to say that he abandoned music altogether. Performances in Boston included a musical accompaniment to a lecture on “The Relationship of Poetry and Music” by my grandmother at the Boston Public Library in April, 1922; piano music in a radio broadcast in October, 1922, "Rhymes and Music for Little Folks," also featuring readings by my grandmother. Similar notices appeared occasionally in the Kingsport Times during their few years in Tennessee, where he ran a print shop. His 1957 obituary states that in addition to teaching and concertizing, he served as director of music for the [New York] Veterans Administration, where he assisted in the training of veterans studying music at Columbia University, Juilliard, City College, and New York University.

But there is nothing to suggest that he ever gave up his day jobs, in which he used his keyboard skills as a “typewriter” and a printer. Music had become an avocation.

Despite the disappointments that beset them, theirs was a happy union. My grandfather was a gentle man and a gentleman, quiet and reserved, but he never passed my grandmother's chair without touching her shoulder. He even enjoyed "helping" her with her garden, which mostly consisted of planting seeds and pulling weeds under her direction.

By the time I knew him, his hands were rusty with arthritis and disuse, and he had grown hard of hearing. He never willingly played the piano in my presence, and when he was cajoled by my grandmother into accompanying family musicales it was clear to me even as a child that his skills had sadly atrophied. Yet so far as I know, he was content with his lot.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed