Although I went back and added a link to the original entry in support of this observation, it is such a quintessential Camp Evans story that I decided it was worth a post of its own.

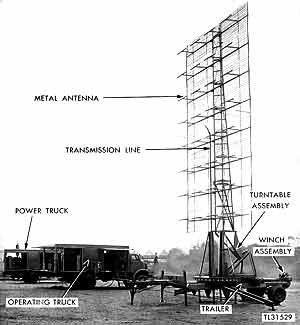

First, lest I left any room for confusion: No, my father had no idea that planes were coming in to bomb Pearl Harbor on the morning of December 7, 1941, as he later stated unequivocally in my oral history interview with him. In fact, there is no reason why he should have known. He was still a newbie at Camp Evans, less than a year on the job. His task was to optimize the equipment then in use, the SCR270, and work on the next step in the series, the SCR271, planned for installation at Pearl Harbor but not yet built.

In the hours during and after the attack, the only ones likely to be privy to information about what had or hadn’t been detected were the members of a select, top secret group that had been working at Camp Evans for years to prevent surprise air attacks on critical vulnerable targets including not only Pearl Harbor but also the Marshall Islands, Midway, the Philippines, the Panama Canal, and others. Needless to say, these men held positions well above my father’s pay grade.

It was an unusually quiet morning, and Lockard took advantage of the lull to train Elliott in the use of the SCR270B. At 7am, the end of their shift, Lockard began shutting down the unit, when suddenly the oscilloscope picked up an image on the 5" screen so surprising he first thought something was wrong - a blip so large it must have been at least 50 planes. As of 7:02am, the blip appeared 132 miles from Oahu. Elliott suggested they report this reading to the Information Center at Fort Shafter, around 30 miles south of the Opana Station. Lockard hesitated at first, but after several minutes of conversation - during which the blip moved another 25 miles closer to Oahu - he gave Elliott the go-ahead.

Tyler's job description was "to assist the Controller in ordering planes to intercept enemy planes...." This was his second time serving in that capacity, the first having taken place three days earlier; he had no training in radar. The Controller and the Aircraft Identification Officer were out of the building having breakfast. Dismissing out of hand the possibility that the blip could actually be incoming enemy aircraft, Tyler scoured his mind for alternative explanations, then remembered that a squadron of B57 bombers - "Flying Fortresses" - was expected from the mainland that morning. With a sigh of relief he uttered five words that haunted him for the rest of his life: "Well, don't worry about it."

By now it was 7:20am. The planes were 74 miles away.

The first bombs struck Pearl Harbor at 7:55am, and only then did the three men realize what it was they had seen on the radar screen. Had the information been passed along, even with only a little over half an hour's lead time, American aircraft might have been dispersed and ammunition readied. Had the Navy been notified, it might have used the information to help locate the Japanese aircraft carriers from which the invading planes took off. Although it is unlikely the main thrust of the attack could have been averted, a response, any response at all, might have demoralized the Japanese by undermining their supreme confidence that they had achieved "tora," a surprise attack - a goal they saw as crucial to their success.

In subsequent inquiries, Tyler was exonerated due to his lack of training and experience. Lockard received the lion's share of the credit and was awarded the Distinguished Service Medal in 1942. Elliott was given the Legion of Merit but declined because he felt, with some justice, that he should not be given a lesser medal than Lockard.

Meanwhile, back at Camp Evans, thousands of miles to the east, members of the team charged with preventing surprise attacks waited on tenterhooks when they learned of the attack on Pearl Harbor, fearing their radar had failed. “If our radar had not given warning because of breakdown, or just ineffectiveness," said First Lieutenant Harold Zahl, "surely part of the finger of blame would point at our group.” He himself had designed and hand-made special tubes for the radar set; had one of them failed? Not until several days later did they receive a call from Washington reassuring them that human error and not equipment failure had been responsible.

* * * * * * * * * *

Although no one knew exactly when or where an enemy strike might occur, the Navy had developed and emplaced ship-based radar units as early as 1940, and by early 1941 the Army team at Camp Evans had set up land-based radar systems in potential target areas around the world. In addition to the Opana station, four other radar units had been installed in Hawaii. This is no secret.

Moreover, the story of the radar signals received by Lockard and Elliott but misinterpreted by Tyler and then ignored altogether is hardly an obscure anecdote buried in tomes read only by military historians or on websites visited only by passionate World War II buffs. On the contrary, it has been retold countless times in popular books and movies over the years. Notable among them: a brief, readable account entitled A Day of Infamy written by Walter Lord and published in 1957 (60th anniversary edition issued in 2001), in which a riveting description of the events that unfolded in the hour before the attack appears; a Japanese-American full-length dramatization of the events of that day entitled Tora! Tora! Tora!, which garnered an audience score of 81% on Rotten Tomatoes; and a 1981 New York Times bestseller entitled At Dawn We Slept, the first volume of a massive trilogy by a history professor named Gordon W. Prange, who devoted not years but decades to the study of a single day in history, generating thousands of typewritten pages of text that after his death were valiantly edited by two assistants-coauthors. (Lockard and Elliott make their first appearance 500 pages into the book.) The story even appears in wikipedia.

So why is it that so many of us still cling to the myth that the US was totally unprepared for the attack on Pearl Harbor?

Perhaps because the Japanese version of the story - that the attack on Pearl Harbor came as a complete surprise to the Americans - is the one that captured the world’s imagination. Mitsuo Fuchida, leader of the first wave of Japanese fighters, famously sent the message “Tora, tora, tora!” to his superiors waiting on the aircraft carrier Akagi - making the communication (intentionally) puzzling to the casual listener since the word tora means "tiger" in Japanese. But “tora” was also a radio codeword combining the two Japanese words totsugeki and raigeki, a phrase meaning "lightning attack”; to those in the know, “Tora, tora, tora” had nothing to do with big cats and everything to do with having delivered a bolt from the blue. And why shouldn’t the Japanese have believed this? After all, from their point of view there was no indication that anyone had the slightest inkling that an attack was underway. No defense was mounted, no evasive action was taken, thereby allowing the Japanese to punch above their weight at Pearl Harbor.

Or perhaps it’s because we collectively prefer the metaphor of the sleeping giant awakened to the less heroic conclusion that three undertrained, inexperienced men had been entrusted with a new technology, and that but for human error, the encounter might have taken a somewhat different turn.

What is lost in the myth-making process is perhaps a minor footnote to the overall arc of the Pearl Harbor narrative but an important chapter in the history of radar. It was the first wartime use of radar by the US military, and, despite the series of mishaps that rendered it useless at Pearl Harbor, it was abundantly clear that this revolutionary new technology was poised to transform the way war was waged. Being neither a military historian nor a radar scientist, I will leave a fuller investigation and interpretation of these developments to someone more qualified than I.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed