“Trust yourself - You know more than you think you do” was its reassuring mantra. Parents had previously been counseled to adhere to a regular schedule of sleep and feeding, even if it meant leaving an infant sobbing for hours. Picking up and comforting babies would only teach them to cry more, argued such experts as Emmett Holt and the behaviorist John Watson. Not only might it delay sleeping through the night, it could also turn them into failed adults, ill prepared to meet the challenges of the real world. Spock, by contrast, encouraged mothers to rely on their instincts, raising their children not by following a series of rigid rules but by responding to the needs of each child as an individual. What a relief this must have been to mothers, especially those who surreptitiously broke the rules, as I can easily imagine my own mother doing, by soothing their crying infants with forbidden hugs and kisses.

Because Spock lived a long life over which his beliefs and positions evolved, it is difficult not to see the book through the prism of its multiple editions. In addition, his controversial involvement in antiwar activism in the 1960s and early 1970s somehow became entangled in people’s minds with his childrearing advice. The conservative preacher Norman Vincent Peale, in an oft-quoted sermon, blamed Spock's "instant gratification, don't let them cry" approach for the violent demonstrations that occurred during that era. More immoderate commentators went even further, demonizing Spock for single-handedly, through some unholy alchemy of his New Left politics and his supposed advocacy of permissive parenting, causing the sexual revolution, selfishness, lust, increases in crime, and the general moral turpitude they believed was destroying American society.

* * * * * * * * * *

Nonetheless, The Common Sense Book of Baby and Child Care was revolutionary. Again, it is difficult to perceive how novel and refreshing it must have seemed to his first readers in Postwar America, because his advice and the version of child development on which it is based have been so thoroughly incorporated into our childrearing thinking and practice. Spock was a pediatrician, not a developmental psychologist, but he was deeply influenced by Freud (he himself underwent psychoanalysis). Indeed, Spock probably did more to smuggle Freud into the popular culture than Freud’s writings could ever have done on their own. (At one point he mentions a little girl who complains to her mother, “But he’s so fancy and I’m so plain” - almost certainly the locus classicus for Mister Rogers’s uncharacteristically graphic song “Everybody’s Fancy.”) As Time's obituary of Spock in 1998 put it, “Surmising that new parents were not yet ready to hear of their infants’ oral, anal, and genital stages, Spock simply advised moms and dads not to get alarmed if a baby sometimes behaved, well, oddly. He had learned from Freud that repression could produce catastrophic adult neuroses. Better, he advised, to wait things out.”

Despite accusations of “permissiveness” (always strongly rejected by Spock himself), his approach can be considered permissive only in contrast with the draconian advice then being offered by Holt and Watson. Dr. Spock expects youngsters to be assigned duties, to put things away, to come to the table when dinner is ready, and to be polite to others. He warns against asking “Do you want to...?” or offering too many reasons when requiring the child to do something. It’s okay for a child to make mudpies (“it enriches his spirit”), but not in his Sunday best. Although no advocate of spanking, neither is Dr. Spock uncompromisingly opposed to it, regarding it as “less poisonous than lengthy disapproval.” The best description is perhaps the one Spock himself chose for the first edition of his book, “common sense.” “Trust yourself,” he told young mothers - and they did.

* * * * * * * * * *

Benjamin Spock was born in 1903 in New Haven CT, the eldest of six children of a rock-ribbed Republican New Haven Railroad official and his wife. Both parents held firm views about childrearing but it was left to the formidable Mildred Houghton Spock to carry them out. She followed religiously the regimen of Dr. Holt, with his rigid schedules for feeding, bathing, and elimination. She also believed in the moral and physical virtues of a Spartan lifestyle that included sleeping in an icy bedroom and attending a preschool where lessons were taught outdoors, even in winter.

After preparatory training at Phillips Andover Academy, he enrolled in his hometown college, Yale, for his undergraduate education. Though not a particularly distinguished student, he was a superb athlete and after crewing at Yale became a member of the 1924 Olympic team. Following his graduation in 1925, he entered Yale Medical School but later, over the objections of his family, transferred to Columbia’s College of Physicians and Surgeons. He also fell in love with Jane Cheney, a lively and socially conscious Bryn Mawr student, daughter of a wealthy silk manufacturer from Manchester CT, whom he married in 1927. Following an all-too-familiar pattern, Jane worked long hours at Macy's to support her young husband's medical education.

Right after the attack on Pearl Harbor, Ben volunteered for military service but was rejected because of back problems. So the Spocks remained in New York, spending their summers in the Adirondacks. A few years earlier he had rejected a proposal by Doubleday that he write a child care book, saying he didn't know enough. Now, with a little more time to relax than his winter schedule permitted, he began to think once again about such a book - a book that would embody his ideas on child care, a book aimed not at experts but at the end users, the parents.

In the summer of 1943 Ben began writing, with Jane at his side. Well into the night, after regular work hours, Ben dictated and Jane transcribed (and often rewrote), sometimes suggesting new avenues to pursue; during the day Jane conducted followup research and solicited expert commentary. Eventually Ben was able to join the Navy but even while he was on active duty, Jane soldiered on with the book, carrying out final negotiations with the publishers, indexing, and hammering out last-minute revisions in the middle of the night via long-distance phone calls with her husband.

The book was an overnight sensation - "only...limited," remarked the publisher, "by an inability to get sufficient paper to supply the demand." Revised editions were issued about every ten years. It was eventually translated into 39 languages. Meanwhile, the Spocks, now a family of four, continued to maintain busy lives. Ben traded his clinical practice for an academic career, accepting many speaking engagements and writing additional books and articles. With a more comfortable income they spent more time vacationing. Jane gamely though cautiously learned to sail in her sixties. As the Vietnam War dragged on, Ben grew increasingly political, even running as a third party presidential candidate in 1972.

Then, in 1975, Ben announced to Jane that he wished to begin a "trial separation." He went out and rented an efficiency apartment for himself. A legal separation followed shortly, then divorce, and within a few months he married a woman 41 years his junior. Jane was devastated.

What went wrong? Apparently neither of the two was easy to live with. “Though he was blessed with a great deal of energy and maintained a warm and pleasant public presence,” said one Spock biographer, “he held impossibly high standards for himself as well as for those around him.” As Jane herself put it, "Ben seems like this outgoing, loving, easygoing person, but he really isn’t. He's a stern person.” His two sons remember him as a cold and remote father, devoid of the warmth and affection he advised his readers to bestow on their children. One told an interviewer his father had always made him feel "judged, criticized, scared, beaten down." "I never kissed them," Spock himself admitted. For her part, Jane spent most of her adult life in and out of therapy. She was dependent on alcohol and Miltown (the tranquilizer immortalized by the Rolling Stones as "Mother's little helper") and suffered from intense mood swings. She also harbored a deep resentment about her husband’s and society’s failure to recognize the extent of her role in creating the child care book and did not hesitate to berate him in public.

In the end, Benjamin Spock apparently lost the will to do the hard work of keeping the marriage together. Their sons were horrified - so much so that they adopted their mother’s family name. Although they could hardly have failed to notice the constant stream of bitter arguments, after 48 years they had long since concluded that was just the way of things.

The prospects for a divorced 70ish woman were of course much more limited than those for her male counterpart. Jane did her best to make lemonade out of the lemons she’d been handed, advocating and running support groups for divorced older women. By and large, however, she lived out her remaining thirteen years a lonely and embittered woman, institutionalized for six months after breaking down altogether and railing against her ex-husband whenever she had the chance. "If it had been a co-authorship, like it should have been," she told an interviewer, "I would have been asked [to be] on televisions shows, too, and I would have been asked what I thought about things. I might have been more of a somebody. But I don't think he could stand it, sharing the spotlight.”

In the fourth edition of the book, just as their marriage was on the verge of dissolution, Spock finally included a generous though long overdue notice of Jane’s participation in the form of a full-page acknowledgment at the front of the book. Was that good enough, or did Jane, as she claimed, deserve more? Ann Hulbert, in her 2003 history of childrearing advice in America, actually becomes quite incensed on Jane’s behalf - though as a reviewer of her book in the New Yorker cynically observed, “If we had a nickel for every twentieth-century author whose wife was an unacknowledged collaborator on his books, we could probably pay for the war in Iraq.”

Nonetheless, although there is no universal standard by which to judge when transcribing, performing background research, fact-checking, recipe-testing, editing, consulting experts, rewriting, and more cross the blurry line into full-fledged coauthorship, a case could almost certainly be made for Jane’s claim. Of the two, she was the scholar. Spock did little if any research on his own and claimed the book “really all came out of my head.” A talented writer and prolific letter-writer, he was probably responsible for the genial, reassuring tone for which the book is justly famous, and of course he had the medical creds to back up his words. But Jane appears to have contributed intellectual content as well as technical and stylistic support. She was the source of his interest in psychoanalysis, for example, and persuaded him that personality formation was fairly well established by the age of two.

Given the breadth and depth of Jane's participation, I doubt that anyone could have quarreled with a joint authorship had it been proposed - and the official inclusion of a woman’s voice might even have increased its appeal (if indeed that were possible, given the book’s astounding popularity). So - let’s just say the decision to go with a sole authorship was a call. Who knows if Jane's life, and their lives together, might have taken a different turn had Ben called it differently, either from the beginning or with the publication of a subsequent edition?

* * * * * * * * * *

So I reviewed my mother’s two baby books on little Cindy for evidence of the childrearing ethos that prevailed before Dr. Spock, and sure enough, there it was: “Cindy started her toilet training on Nov. 19, 1943, her ninth month birthday.” As Spock observed, when a baby appears to be toilet-trained that early, “It’s the mother who’s trained.” Readiness was everything, to Spock's way of thinking. There may be no harm in starting so early; on the other hand, if the mother makes excessive performance demands the child may end up rebelling in his second year. Better to put it off for a few more months.

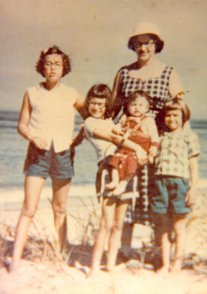

Standing on the bank of the Shark River with my mom and siblings. I'm on the left, slightly apart from the others - a little preadolescent "attitude", perhaps?

Standing on the bank of the Shark River with my mom and siblings. I'm on the left, slightly apart from the others - a little preadolescent "attitude", perhaps? As I prepared to write this essay, I was surprised to discover that the man who shepherded me through most of my childhood stages even had a few words of wisdom about my current life stage. In his autobiography Spock on Spock, he described his attitude towards aging as “delay and deny” - an approach I too have found useful.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed