But what was a little girl in a small coastal New Jersey town doing with an exotic Hawaiian stringed instrument?

The ukulele is a plucked stringed instrument belonging to the lute/mandolin family. Although it is sometimes thought of as quintessentially Hawaiian, along with hula dancers in grass skirts and leis, it was actually developed in the 1880s by Portuguese immigrants who came to Hawaii from Madiera and Cape Verde, based on similar guitar-like Portuguese instruments. Its place in Hawaiian music and culture was cemented by the support of King Kalakaua, who enthusiastically promoted the instrument and made it a central part of performances at royal gatherings.

The US mainland discovered the ukulele in 1915, at the Hawaiian Pavilion of the Panama-Pacific International Exposition in San Francisco. Being cheap, portable, and relatively easy to learn to play passably well, the uke quickly passed into the popular culture, appearing in film and becoming a mainstay of jazz, country music, and American song.

The life trajectories of two men converged to turn the ukulele into the musical phenom it was to become in the post World War II era:

The first was Arthur Godfrey, folksy host of a series of eponymous radio and then television variety shows. My Aunt Phyllis, my mother’s younger sister, always claimed to dislike Arthur Godfrey because, she said, he laughed at his own jokes, but whenever his show came on the air, she poured herself a cup of coffee and sat down to listen. We often spent several days with Aunt Phyllis and her family in Worcester MA during our summer vacations, and when “the Old Redhead” (as he called himself) came on we stopped what we were doing and joined her in her kitchen. He was famous for poking good-natured fun at his sponsors’ products. The off-script commercial I remember best was his test of the proposition that Lipton teabags could be reused for several days in a row. The second day came and went without too much comment, but by the third day his reaction was simply “blecch.” He got away with it because it was known he would not accept a sponsor whose products he didn’t personally enjoy, and because (bottom line) it sold those products.

Arthur Godfrey’s Talent Scouts started in 1945 as a radio show. From 1948 to 1958 the show was transferred to the next big thing, TV, but continued to be simulcast on the radio. From 1949 to 1959, he also broadcast Arthur Godfrey and his Friends, also known as simply the Arthur Godfrey Show, which featured many of the Talent Scout winners including Pat Boone, Eddie Fisher, Tony Bennett, Connie Francis, Patsy Cline - and Julius LaRosa. LaRosa, in fact, triggered a downturn in Arthur Godfrey’s popularity in 1953 when Godfrey fired him on-air, without warning, for exhibiting too much independence or, as Godfrey put it, “a lack of humility.” That was not how underlings were supposed to be treated in those days, and it didn’t sit well with his fans. But during his radio days and his early years on TV, everything he touched turned to gold. He raked in millions of dollars for his bosses and as a result was probably the first media star to become truly wealthy.

It is sometimes said that apart from being an uber-genial host, Arthur Godfrey was devoid of any special talent. This isn’t strictly true; he was an accomplished ukulele player who even gave on-air ukulele lessons. “If a kid has a uke in hand,” he assured parents, “he’s not going to get into much trouble.” Too bad color TV had not yet come in; black-and-white could never do full justice to Godfrey’s shock of red hair and his colorful Hawaiian shirts as he strummed his big baritone ukulele. Through him, the ukulele found a welcome in millions of American homes.

The second contributor to the postwar ukulele craze was an Italian luthier named Mario Maccaferri, until then best known for designing the guitar played by the legendary Romani musician Django Reinhardt. Maccaferri was also a classical guitar virtuoso in his own right, perhaps in a league with Segovia, until a freak swimming accident in 1933 injured his right hand and ended his performing career forever. He continued making stringed instruments, however, and also started a business in France making high-quality reeds for woodwind instruments.

In 1939, Maccaferri fled with his family from war-torn Europe to the US, struggling to maintain his reed-making business (now christened the French American Reed Manufacturing Company) in the Bronx, despite a wartime shortage of the French cane he needed to make his product. Then a visit to the NY World Fair introduced him to a new concept - plastics! - and fired his imagination. He started experimenting with polystyrene reeds and found that indeed, they worked pretty well, especially when wooden reeds were unavailable. Endorsements from clarinetist Benny Goodman and other Big Band musicians brought him a good customer base. Emboldened by his success, he went on to found his own molding and manufacturing company, Mastro Industries, which produced cheap plastic versions of everything from clothespins to toilet seats.

Everything went well until it didn’t. Eventually, a combination of increased competition, increased demand for more upscale fixtures, and increased availability of alternative construction materials started making serious inroads, and Mastro Industries found itself on the skids.

That’s where things stood when a chance poolside encounter between Mario Maccaferri and Arthur Godfrey in a Florida hotel rocked both their worlds - and ended up putting ukuleles into the hands of millions of American kids including mine. The two men knocked back a few drinks, played a couple of impromptu duets, and bemoaned the lack of affordable mass-produce-able ukuleles. Maccaferri had long dreamed of making a plastic ukulele but lacked the capital to proceed without some promise of success. When Godfrey replied that he could sell a million of them, Maccaferri was inspired to revive his dream and redouble his efforts to finance this new venture.

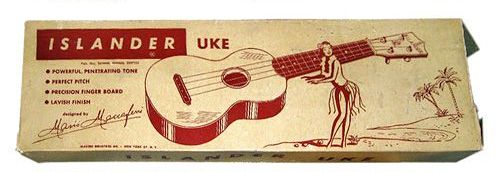

Although Maccaferri’s earlier attempts to make a plastic guitar and his subsequent attempts to make a plastic violin were neither commercial nor artistic successes, it turned out that plastic was well suited to producing an instrument-quality ukulele. After extensive research, he settled on Dow Styron, which gave him the warm wood-like tone he was seeking, and strung it with nylon strings made by DuPont. He called his creation the Islander and packaged it with a pick, a tuning tool, instructions, and a songbook. It sold for $5.95.

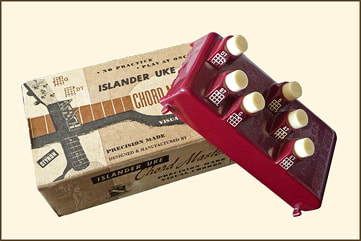

It all comes back! The Chord Master was supposed to be attached with two rubber bands, and I sort of recall having trouble making the darn thing stay put - probably more a commentary on my technique than on the device itself. Again stirring up some long-dormant memories, I think there was an additional reason for my Chord Master woes: The buttons are labeled D7, B7, and G on the upper row and D, A7, and E7 on the lower row - indicating that the Islander was supposed to be tuned not to G-C-E-A, as I did, but rather a whole tone higher, to A-D-F#-B. That had to be confusing to anyone who was looking for the chords you’d expect to use in the key of C.

For whatever reason, in the end I ditched the Chord Master. Instead, I mastered a handful of chords and then limited my repertoire to songs that required only those chords.

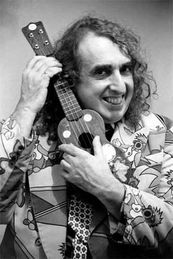

Tiny Tim

Tiny Tim But the ukulele just won’t stay dead. It has enjoyed at least two revivals since then. The first was in the 1990s, when a new generation of instrument makers started appealing to a new generation of musicians, most of whom had forgotten Tiny Tim and maybe even the Beatles. The second is now in progress, fueled by the rise of youtube ukulele artists like Hawaii native Jake Shimabukuro, whose videos routinely go viral.

Don’t look at me, however. I haven’t played a uke since the 1950s, and my once-cherished Islander has long since disappeared into the mists of time.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed