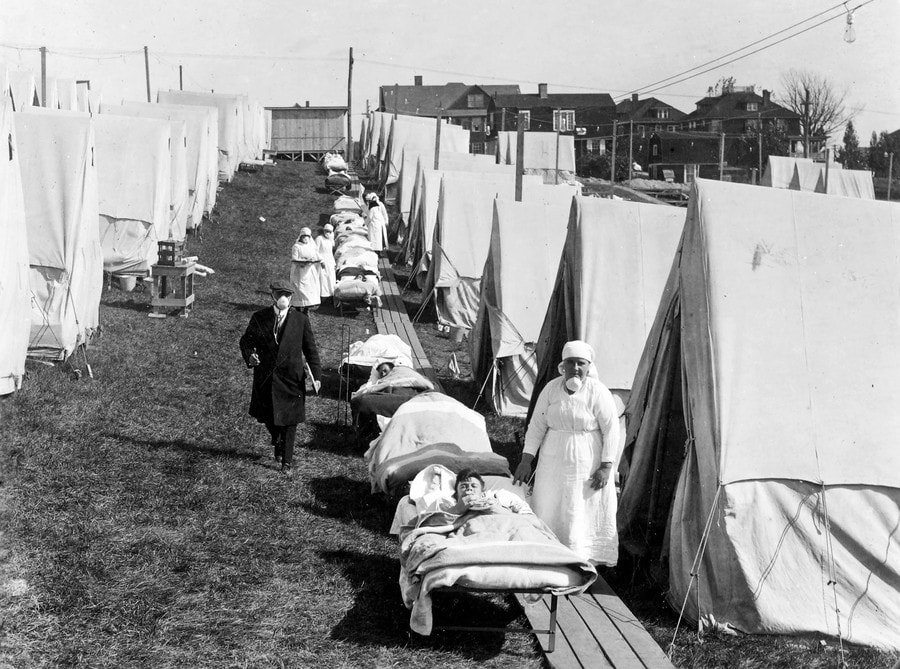

So now that the book is out there, what about this blog? When I first started writing it, my husband expected me to exhaust my material after five or six entries. Although he is right about most things, he was pretty far off on that one. Five years and several dozen posts later, I still find myself with a file folder full of fascinating topics waiting to be addressed—Fitkin Hospital, for example, where all four of my parents’ children were born, now part of a regional medical center that reflects the evolution of health care and health care delivery throughout the country; or Ocean Grove, a Methodist Camp Meeting resort with strict blue laws, housing stock rented by residents via 99-year leases, and streets closed to traffic on Sundays; or the fascinating history of the Army Signal Corps. Just to name a few.

I also have another file folder full of other writing projects that have nothing to do with Project Diana, projects I hope to work on while I still can.

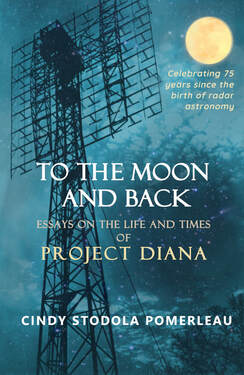

I have reluctantly decided that the time has come to shelve this blog at least for the moment, and to devote my time and attention to those other projects. This is my last post to this blog; as of now, “To the Moon and Back” is officially archived.

Meanwhile, I have completely revamped the parent website, rechristened Project Diana: Radar Reaches the Moon, as befits the only website devoted entirely to Project Diana. Comments, suggestions, and corrections welcome.

I am currently devoting my blogging energies to my new blog LOL, which can be accessed via my author website. It will feature my current work, previews of work-in-progress, what I'm reading, what I'm thinking about, and what's going on around me—likely including more than an occasional nod in the direction of Project Diana and my Jersey Shore childhood. I invite you to join me there.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed