As I recounted his sad story and remembered the family’s grief (still vivid in my memory though I was only seven at the time), I started thinking about all those others who, though they may not have served in uniform, were also required to make heroic sacrifices. I thought of my cousin's parents, whose hopes and dreams for their son were shattered in that long-ago moment. And I thought of all those whose lives have been deflected by a call to arms, individuals without whose material and emotional support such missions, however heroic or futile, could not be carried out.

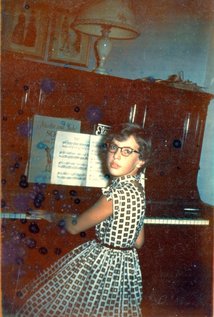

Of no war is this truer than of World War II, perhaps the last war in American history to have had almost universal public support. It was not only the Great War, it was also the Good War, a war in which we felt clearly aligned against the forces of evil. In his book The Greatest Generation, Tom Brokaw included within the scope of that term not only those who went off to fight on foreign soil but also those whose productivity at home made a decisive contribution to the war effort. It included not only my father-in-law, who spent most of the War as an Army Surgeon in Italy, but also his wife, left on her own to raise a child - my husband - who essentially never knew his father until he was four years old. It included my stepmother Rose, a true Rosie who put her career as a musician and a grade school teacher on hold to work as a welder at Grumman Aviation on Long Island. These were sacrifices made, and made willingly if not gladly, because Americans saw it as a collective commitment, not just a head count of troops sent by the President to fight and perhaps die in lands whose names they could barely pronounce. As Tom Brokaw put it, it was the “right thing to do.”

My father’s family is a case in point. It has often struck me as interesting and perhaps even a little odd that my father and his two younger brothers all served in somewhat unconventional capacities.

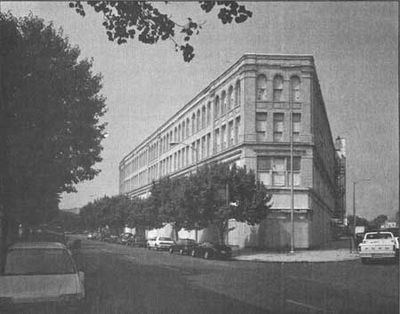

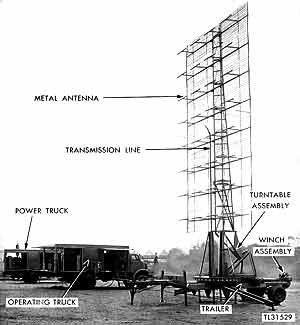

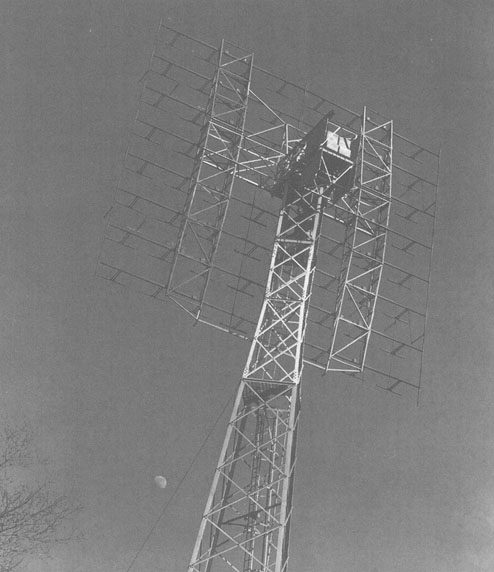

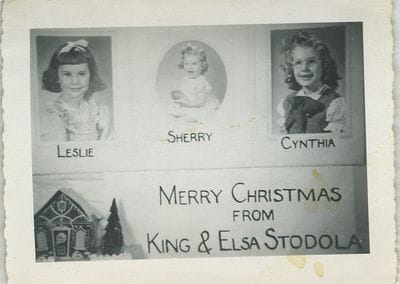

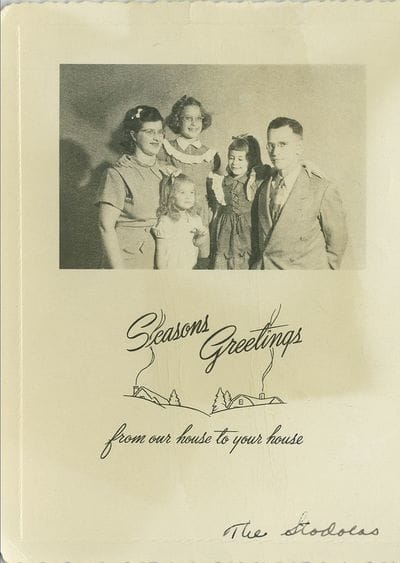

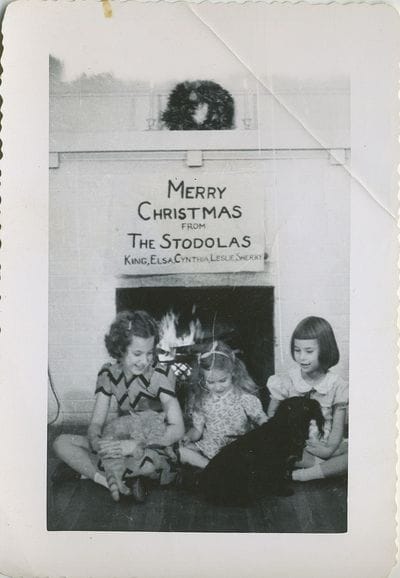

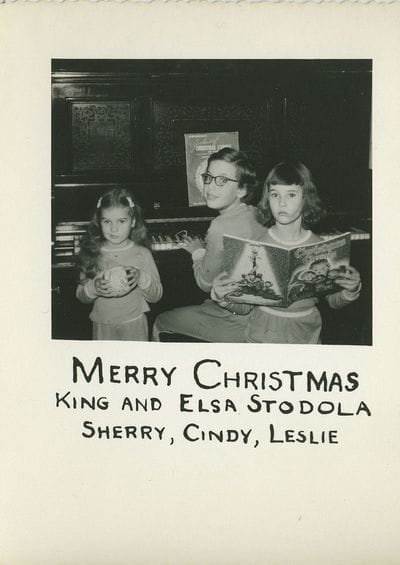

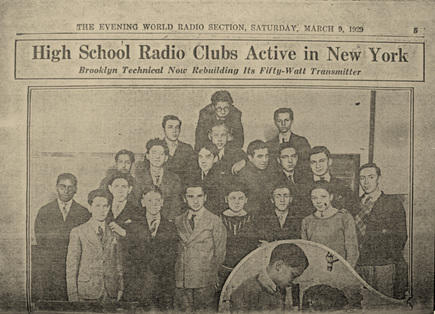

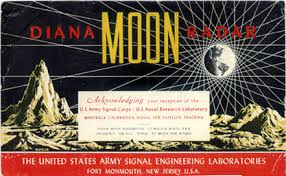

- My father, King Stodola, as anyone who follows this blog is aware, worked for the Army as a civilian scientist. There was never any question of his being sent overseas because his work in developing radar was considered essential to the war effort and in the event proved crucial to the Allied victory.

- Syd, the youngest of the Stodola brothers and the only one to don a uniform, served in the Coast Guard, the smallest by far of the four branches of the American military and a bit of a neglected stepchild despite a long tradition of keeping its big promise, Semper Paratus (“always ready”). “They don’t get half the credit they deserve,” said one man of his Dad’s Coast Guard career.

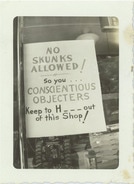

- Quentin, the middle son, chose the most controversial path (even within his own family), registering as a Conscientious Objector - not a popular position especially during World War II, and even more especially for someone who was not a Quaker.

* * * * * * * * * *

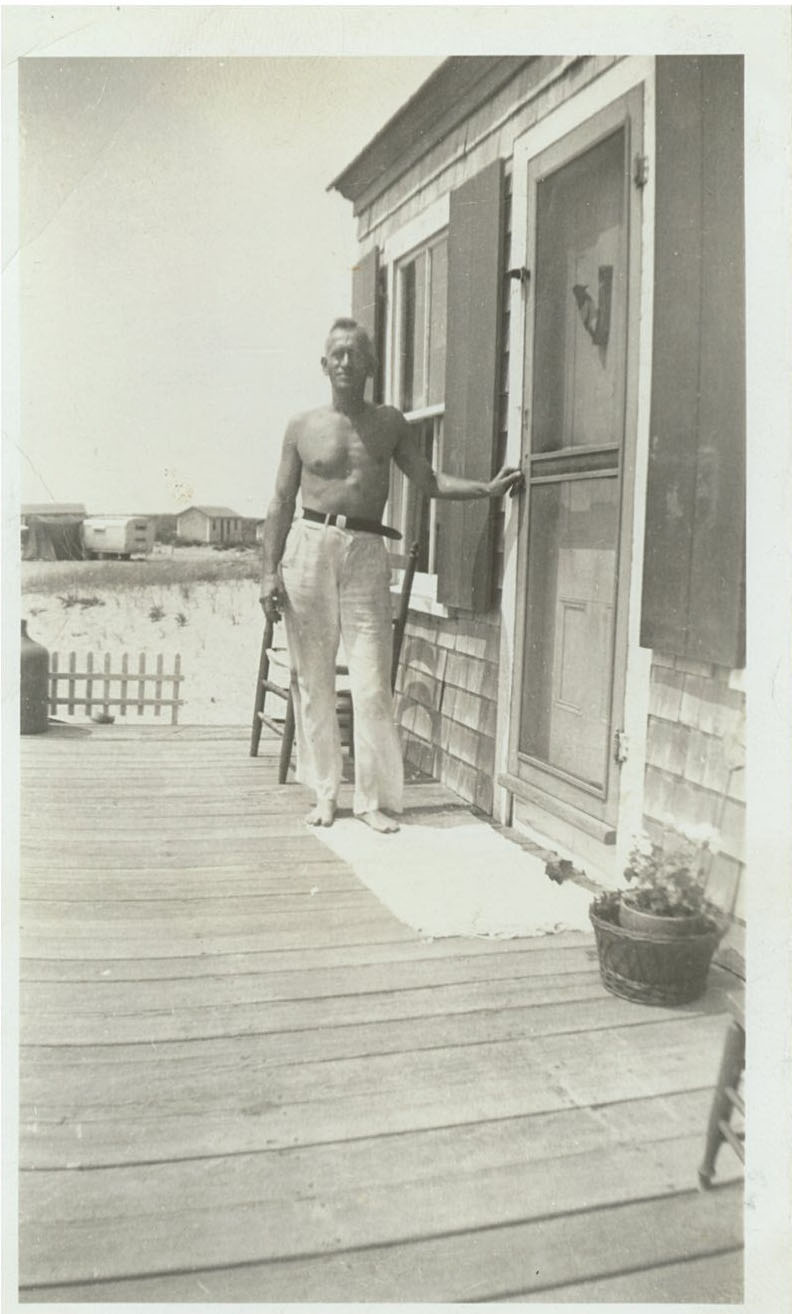

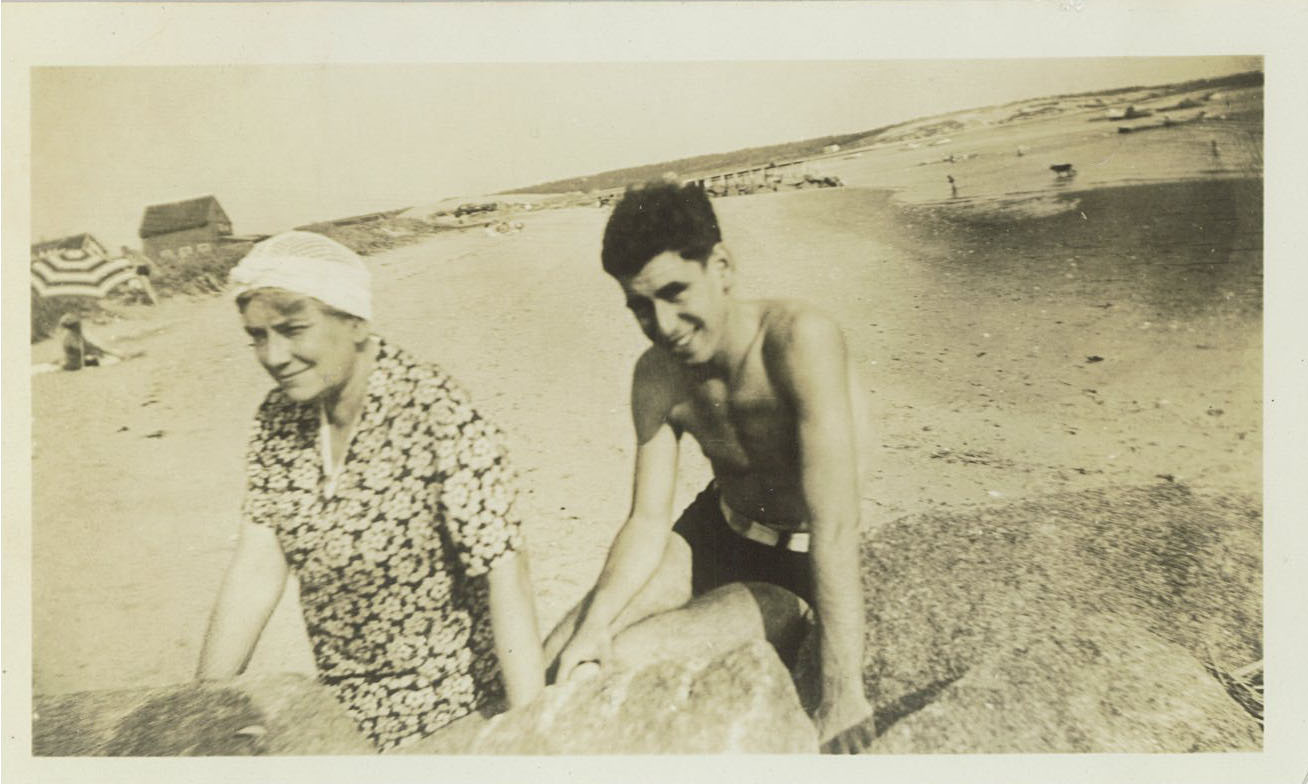

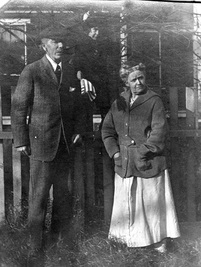

In recognition of Memorial Day, I decided to delve a little deeper into the contribution of these three young men to the war effort, and to invite their mother, Beatrice King Stodola, to help me out. Almost as though she were anticipating my queries, my grandmother was prescient enough to keep a journal entitled “Saint Barbara’s Hill: A Cape Cod War-time Log,” in which she documented her joys and (many!) anxieties, as well as the comings and goings of her “boys,” during her annual stay at Shining Sands, the family’s beloved vacation cottage, in the summer of 1943. (My poor grandfather, except for an occasional stolen weekend getaway and a longer stay later in the summer, remained sweltering at his office job in New York City - but that’s a story for another day.)

I feel particularly blessed to have this journal because it gives me a glimpse of the adult relationship I might have had with my grandmother had she lived long enough. For example, on Thursday, August 5, she wrote, “My husband swims every day, but [I] must confess I only go in when I feel like it, which is not very often.” Friends, does that sound like me or what? I'd enjoy swimming so much more if only I didn't have to get wet! And again, a few days later, on Friday August 13: “I had rather a disturbing letter from one of my sons [Quentin]. He may not bring his wife with him when he comes on furlough. It’s just too bad! Received a letter from the wife of another son [King] with a picture of my grandchild – bless her. It was so nice to have daughters when my sons married.” As the mother of daughters, I feel exactly the same way, mutatis mutandis, about my two sons-in-law!

Despite her ongoing concern about German submarines and suspicious strangers, however, she seemed to be in greater danger from target practice conducted by the American military on the nearby dunes. The serenity of her vacation retreat was incessantly violated by the sound of the “ack-acks” in the (not-so-distant) distance - accounting for the title of her journal: “We shall have to change the name of this hill to Saint Barbara’s Hill. She’s the patron saint of gunners I am told.” During one of his weekend visits, my grandfather retreated several times one afternoon from the task of putting up screens on the second floor windows because the tracer bullets aimed at the target (towed by an airplane!) were just too close for comfort.

But the most obvious impact on her family, of course, was the involvement of all three of her sons in the war effort. They are here “only in spirit, just now,” she notes. “‘Uncle Sam’ keeps them busy at the moment.”

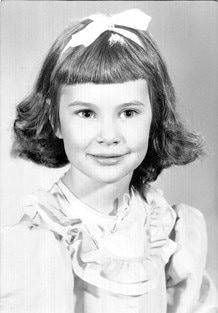

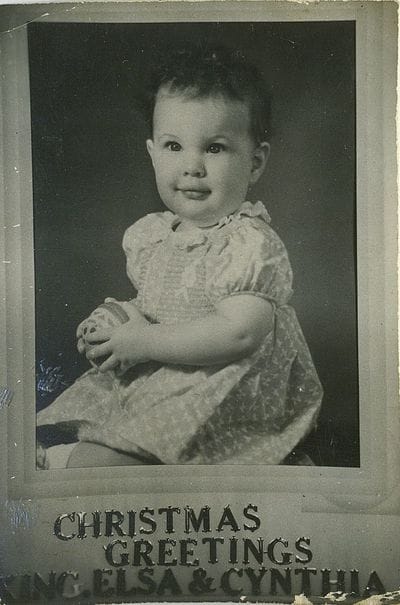

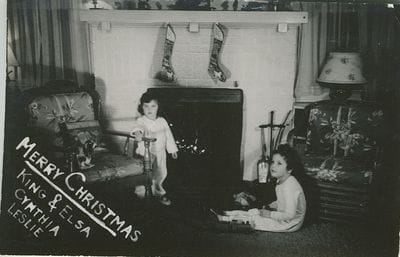

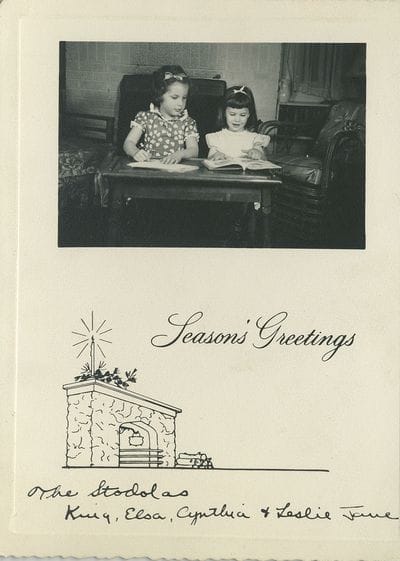

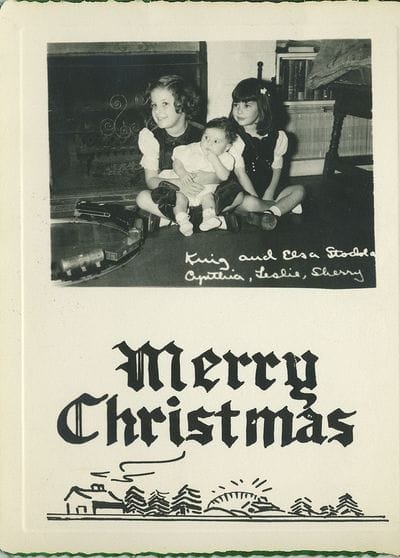

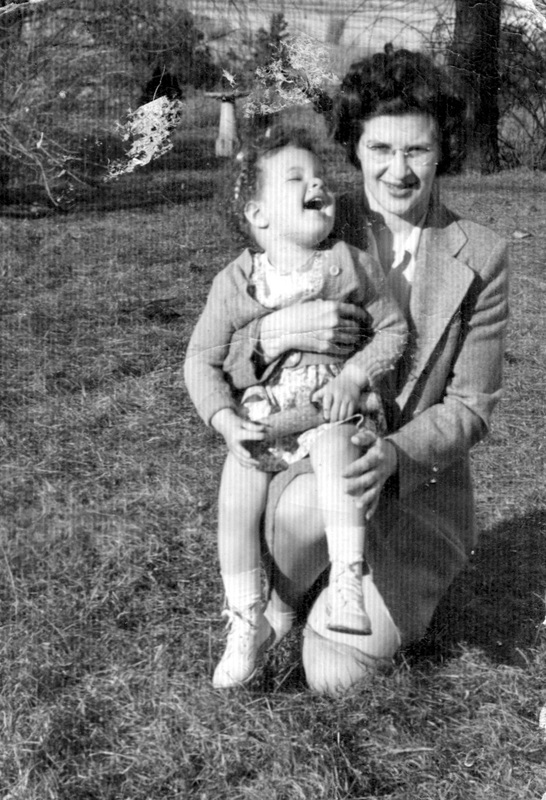

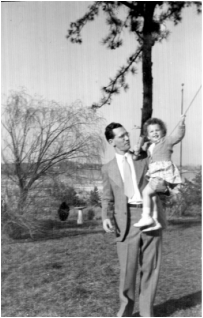

My father, working overtime at Camp Evans and spending what little spare time he had fulfilling his role as a new father, evidently never made it to the Cape at all that summer. My mother, however, kept the lines of communication open. On Thursday July 29, my grandmother wrote, “Pictures came today of our first grandchild [that would be me] – five months old. We have all been wondering whom she looked like but these snap-shots certainly look as her dad, my oldest son, did when he was a baby.”

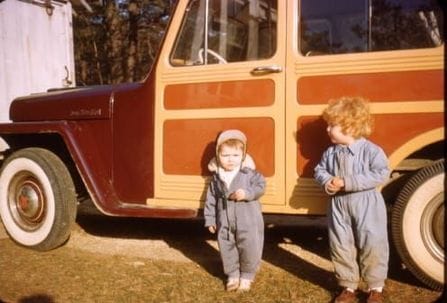

My Uncle Syd, a carefree bachelor, seems to have shown up whenever he had a few days’ leave. On Saturday July 24, she wrote, “About noon a telegram came from our Coast Guard son saying he would be in this afternoon between three and four – probably a forty-eight hour leave. He arrived on the four o-clock bus from Boston. The rest of the day was spent in TALK and EATS.... After we pulled the black-out curtains we played three-handed bridge, in the midst of which the mother cat walked in proudly carrying a half-grown rabbit. The little thing seemed partly alive so the Coast Guard rescued it and put it out in the silver leaf." And then the next day, "We went out early this morning to see if the rabbit had escaped safely. It had! Somehow saving the life of a rabbit, and guns on the next hill, seems rather incongruous. …The Coast Guardsman left on the late bus very proud of his new stripe – he is now a seaman first class.” And again, on Sunday August 8: “We sat on the edge of the dune with [Syd] and watched groups of P.T. boats on the horizon…. [He] left at 7:30 with a package of cigarettes given him by the owner of the nearby village store. Those little things mean so much more to the boys than anyone realizes.”

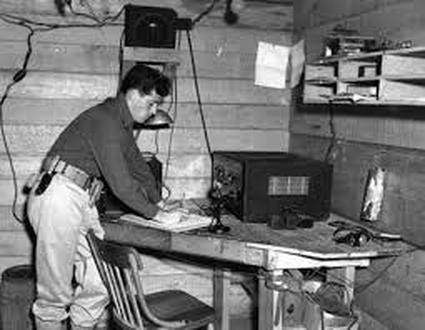

About my Uncle Quentin, whom I later came to know very well and whom I would describe as a perfect blend of severity and saintliness, I will leave the last word to my grandmother, who got it exactly right in her comments on Monday August 16: “[Quentin] is leaving this week-end to work for the Government in New Mexico. He has been at a C.P.S. [Civilian Public Service, which provided American Conscientious Objectors with an alternative to military service during World War II] camp in New Hampshire since shortly after the war began. I stand by all of my sons like the Rock of Gibraltar, whatever their beliefs. Who am I to say what is right or wrong when it comes to creed or religion? He has lost eighteen pounds being a human guinea pig in a diet experiment for the Harvard Fatigue Laboratory. They are trying to find the best food to send to the starving millions abroad. Last year he was a guinea pig for a louse experiment conducted at the camp by the Rockefeller Institute. In the last war thousands of boys lost their lives through disease spread by lice. The powders developed in this experiment came in time to be used by our boys in Africa.”

I

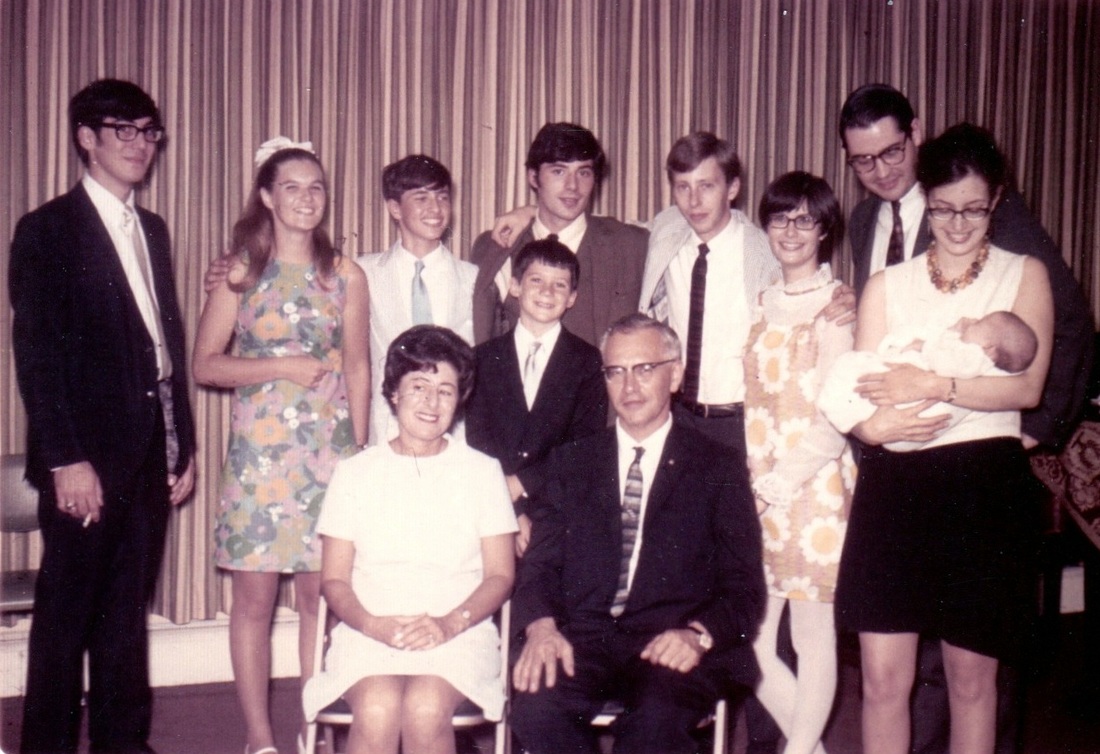

I Quentin's granddaughter Sarah Wald and I have donated his collection of photos from his experience as a Conscientious Objector, of which this was one, to the Swarthmore College Peace Project.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed